Introduction

The Sino-American relationship is incredibly complex in the modern-day, consisting of a strong military and intelligence apparatus with differing national interests, but also extremely intertwined economies as the two large powerhouses of the world. However, there are many points of friction from economic, political, and military perspectives. As Chinese economic and political prowess has grown, it has sought to expand its influence outside of its borders, particularly in the South Indo-China region and the greater Asia. It is a matter of a transitioning power dynamic, as China is seeking to achieve the world hegemony and influence that the United States holds under the Hegemonic Decline Theory.

A large element of Chinese expansion is the use of its military forces, which include intelligence activities as well. China has increasingly ramped up its military budget to $215 billion as the second largest in the world, rapidly developing and modernizing its effective military institutions and capabilities (Ciovacco, 2018). China creates an all-encompassing threat to the national security of the United States in the South Indo-China region and domestically, requiring significant intelligence efforts to recognize and address the tactical and strategic threats through strategies including the use of ISRs, foreign intelligence partnerships, and counterespionage efforts.

Importance of Asia-Pacific Region

The U.S. holds enduring interests in the Asia-Pacific region and has had a long history of presence and operations. The region is significant due to the strategic geographic location of South-East Asia to key areas of operations where security issues have may arise such as the Middle East, and North-East or Central Asia. Furthermore, the Asia-Pacific has significant economic opportunities, rich in natural and energy resources. Due to globalization, the area is home to the world’s fast-growing and healthy economies, many of which are U.S. allies as well as busy ports and shipping lanes which are vital to supply chains for U.S. firms. The South China Sea holds tremendous strategic importance withholding potentially large oil and gas reserves as well as being a chokepoint of more than $5 trillion worth of trade passing through. Given the geostrategic importance of the area, achieving control of it has been a key aspect of security strategy for both the U.S. and China. As the U.S. implements its ‘Pivot to Asia’ initiative, it is attempting to rebalance using strong soft power components of a strategy of engagement combined with characteristics of containment of China (McKenzie & Skiba, 2016).

Security concerns and challenges are prevalent in the region such as military build-ups, piracy, and proliferation of nuclear weapons. U.S. economic and security interests are inextricably linked from Western Pacific into other regions such as South Asia, the Indian Ocean, and the Middle East. The U.S. holds a strategic commitment to its allies and partners in the region, with close alliances with Thailand, Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, and Australia while also partnering with Indonesia, India, and Singapore. All of these countries are currently experiencing tremendous pressure and threats from Chinese expansion and flex of force, relying on U.S. protection. The U.S. seeks to protect all the above interests by projecting its presence in the region through diplomatic, informational, military, and economic instruments of national power (Torelli, 2013).

Intelligence Surveillance Reconnaissance (ISR)

ISR is a range of strategic surveillance methods that the United States deploys in domains of air, space, surface, and cyberspace to gain an accurate and timely knowledge of current or potential adversaries. ISRs are capable of collecting a wide array of information that can be used to analyze motivations, intentions, military capabilities, and the posture of the adversary. Surveillance is key to supplement decision-makers with accurate and timely information with indications, warnings, targeting support, and a comprehensive understanding of the battlefield. Furthermore, ISRs identify gaps in intelligence demonstrating where the increased focus is necessary to gain knowledge and enable decision-making (Torelli, 2013). ISR is a vital system for intelligence collection and assessment in the Western Pacific, critical for early detection of Chinese military build-up or expansion in geopolitical contexts or potential preparation for conflict.

Chinese Threat

As mentioned earlier, China is rapidly but strategically building up its political, economic, military, and intelligence capabilities to achieve geopolitical hegemony and gain influence in the region and globally. China’s focus on developing and acquiring modern weaponry to establish itself as global military power poses an increasing threat to American defense superiority in the Western Pacific region. The rapid military rise and its effects are aimed primarily at United States strategic allies in the region such as South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan.

China is gradually expanding the use of its People’s Liberation Army (PLA) as an instrument of national power, beginning with counter-piracy operations and patrols, to creating island bases in disputed territory. While Chinese leadership is focused on preserving internal stability, they are also projecting Chinese dominance across East Asia and the Western Pacific driven majorly by the goal of reunification and assimilation of Taiwan (Ryan & Sonne, 2019).

Types of Intelligence Collection Systems

Their current trend in ISR collection is towards multi-sensor, multi-mode systems. A typical range of sensors may include: electro-optical (EO) full-motion video (FMV), infrared (IR) FMV, synthetic aperture radar (SAR) with ground-moving target indicator (GMTI), inverse SAR (ISAR), hyper-spectral imaging (HSI) sensors, signals intelligence (SIGINT), electronics intelligence (ELINT), and automatic identification systems (AIS). The suite of sensors is delegated to a single sensor payload operator. Most popularly, this includes Unmanned Aerial Vehicles the likes of Global Hawk and Predator drones. However complex manned aircraft systems are utilized such as the iconic U-2 reconnaissance plane or the large complex E-8 Joint STARS intelligence-gathering aircraft. Many of these sensors can be installed on maritime carriers too such as ships or submarines as well as stationary ground and seabed installations for long-range sensors (Doerry, 2016).

A significant challenge is a poor integration between sensors on a single operator. The radar is typically multi-modal including various SAR, GMTI, and maritime search models. The operator needs to select manually which mode to operate given the circumstances such as time of day, weather, as well as objectives of the mission. Therefore, this is done to the exclusion of other types of modes or sensors, and coordination has to be done manually. As a consequence, more intuitive and easier to use sensors such as EO FMV are given preference with others being underutilized (Doerry, 2016).

Requirements of ISR Systems

The effectiveness of ISR systems is determined by the ability to handle large-scale, distributed operations. The greatest ISR contribution must come from the reduction in the F2T2EA (find, fix, track, target, engage, assess) mission-cycle time. Furthermore, rapid, ad hoc integration of platforms into strike forces and fast-reaction mission planning is necessary. Models demonstrate that force attrition and asset requirements can be reduced if the enemy is engaged at the onset of aggression. Therefore, ISR technologies must present opportunities to improve the time available for detection and reaction to a threat (National Research Council, 2006).

U.S. military has powerful modern airborne ISR systems such as Global Hawk, Predator UAVs, and E-2C have highly technical advanced sensors capable of SIGINT and other surveillance with enhanced air, ground, sea-surface, and subsurface images. IMINT systems provide photographic coverage over denied territory enabling precise geodetic positioning of targets. SIGINT systems offer global coverage and provide geodetic positioning of platforms emitting radio frequencies. Each of the earlier identified sensor carriers has their kinematic capabilities and support various types of primary missions. It is necessary for forces such as the Navy that is a key force in containing Chinese expansion to have access to data from these capabilities (National Research Council, 2006).

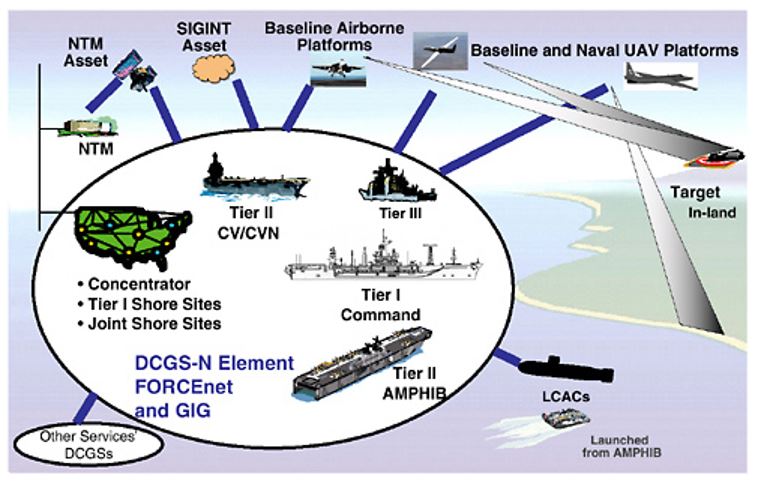

The principal function of ISR is to find, fix, and track both friendly and hostile forces, assessing damage to hostile targets in the area of interest. Collection (sensing) of information, tasking of sensors, integration, interpretation, and exploitation of sensed information. Current ISR capabilities fall short in sensor tasking and data exploitation. With the development of Distributed Common Ground System (DCGS) as a control center and other modern technologies, improvements in automated data processing and interpretation are expected as a requirement of ISR. Furthermore, ISR systems produce a collection of information from a disparate set of uncoordinated sets of national, regional theater, and naval sensors. However, potential knowledge from the information is rarely achieved since tactical commanders have neither the staff, skills, or tools to recognize the relevance of reports and interpret them accurately. The ISR architecture must be unified and coordinated to ensure information dissemination, processing capabilities, and targeting systems that can be scaled up for major commands or scaled down for installation on tactical platforms (National Research Council, 2006).

Challenges

The biggest challenges to ISR implementation in the South Indochina region are China’s anti-access and area denial strategy as well as lack of developed ISR infrastructure. It directly challenges ISR’s freedom of movement and action in the Western Pacific theater. China’s anti-access and denial strategy is focused on disrupting, delaying, or potentially destroying U.S. projection forces, preventing them from penetrating Chinese sovereign territory or its strategic military locations. These may include using advanced integrated multi-domain weapon systems to conduct kinetic attacks on aerial vehicles or satellites as well as cyberspace attacks on networks and potentially indirect disruption of logistics, transportation, or support forces. This strategy is aimed at disrupting U.S. intelligence efforts as well as coercively dissuading regional allies from granting their territory to launch U.S. military and intelligence operations.

Chinese anti-access strategy directly puts at risk U.S. ISR projections in the region since for optimal ISR operations there have to be advantageous operation locations, reliable command and control networks, robust processing and dissemination architecture, as well as long-range sensors. All of these are critical components that are consistently at risk due to China’s strategy and efforts (Torelli, 2013).

Intelligence Surveillance Reconnaissance Application

Comprehensive ISR requires a regional security architecture and network, which currently does not exist for intelligence despite numerous partnerships the U.S. has in the region. Countries rely on organic ISR capabilities and bilateral ISR agreements, but often the concerns and requirements exceed a country’s capacity and capabilities to identify, disseminate information to allies, and address said threats. While the U.S. shares many common objectives and even equipment and contingencies with allies in the region, the ISR agreements are bilateral rather than multilateral, severely limiting the full capabilities that the ISR regional architecture can serve in addressing the Chinese threat (Torelli, 2013).

Modern military conflicts, particularly with China, will consist primarily of long-range warfare such as missiles and air superiority. However, with effective intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance, targeting information cannot be acquired and such weapons will have no meaningful strategic effect. Currently, the U.S. and its regional allies have not cultivated its use of ISR in various contexts such as long-range sensors, manned and unmanned assets, and both mounted and space-based imaging tools. Transferring assets from the dwindling conflicts in the Middle East, establishing ground and seabed installations with regional allies, and developing long-endurance, medium-altitude drones, the U.S. can begin to crack China’s anti-access barrier.

The United States needs to provide persistent and intrusive ISR to provide indications, warning, and situational awareness, and prevent strategic surprise. In the age of nuclear-armed forces and a powerful adversary such as China, deterrence is the key strategy. However, that requires strategic leadership to revisit current conventions of using military hardware and invest heavily in ISR to possess up-to-date and effective intelligence for effective and competent decision-making.

Foreign Intelligence Partnerships

U.S. intelligence at all levels relies on close relations and communications with foreign partners with shared national and regional security interests. Although acknowledged, the benefits of international collaboration are not widely recognized, partially due to the sensitivity of intelligence collection but also due to political factors. The current Trump administration has greatly challenged the status quo of international relations and diplomacy, making it difficult to maintain the same level of trust and cooperation with partner nations in the Western Pacific region. The U.S. should seek to foster foreign intelligence partnerships based on professionalism and credibility to ensure coverage of national security priorities and maintain the exchange of intelligence relationships with military allies and potential partner nations.

Cooperative Programs and Partner Nation Capabilities

The intelligence community maintains liaison relationships with many countries for multilateral intelligence collaboration. A multilateral agreement is an accord among three or more parties, governments, or agencies for the collection, protection, and analysis of both public and secretive information to reduce the uncertainty of decision-makers in foreign policy issues or national security interests. In a globalized world, there is no clear-cut adversary as during the Cold War. The United States maintains liaison intelligence relationships even with adversaries such as China or Russia for common security concerns such as counterterrorism (McGruddy, 2013).

Intelligence cooperation consists of an exchange of data, shared training, and joint field operations. U.S. national security interests have long relied on international cooperation among intelligence services, particularly key regional, NATO, and Commonwealth allies despite changing global circumstances or adversaries. There are some challenges to foreign intelligence relationships. Conflict interests may lead to adversaries gaining access to critical sensitive information and strategies. Furthermore, poor information gathering and moral hazards from foreign intelligence services may not be on par with values and methods that do not meet U.S. standards. However, there are numerous benefits from partner nation capabilities as well, including:

- Access – information unavailable to direct U.S. penetration

- Speed – gather crucial data giving U.S. time to respond

- Insight – cultural understanding of foreign governments

- Ability to perform direction action – directly interfere on behalf of U.S. interests

- Cover for U.S. interests – masking U.S. intelligence activity (Rosenbach & Peritz, 2009).

Exchange of Intelligence and Intelligence Sharing

The exchange of intelligence among partner nations can take on various forms, ranging from warnings and tips to detailed reports on persons, locations, or nations of interest. Intelligence sharing covers a variety of national security priorities such as national defense, emerging threats, counterterrorism, cybersecurity, and international threats. There are significant benefits, some of which overlap with earlier positive aspects of partner nations, including early warnings of an attack, corroboration of national resources and intelligence mechanisms, accelerated access to a contingency area, expanded geographic coverage, and diplomatic backchannels (DeVine, 2019). The U.S. even with all of its resources and expanded intelligence and military networks would not be able to effectively manage intelligence collection and mitigation efforts on its own.

A foreign intelligence partner nation may provide to the United States on persons of interest, national security concerns, or serious threats of counterintelligence efforts that will be discussed in the next section. Employing special collection techniques, a mutual adversary such as Russia or China is targeted. Sharing finished intelligence derived from multiple sources is less risky at identifying sources as well as more comprehensive and typical for multilateral intelligence relationships (DeVine, 2019).

Joint Training

Joint training and operations are a key cornerstone of intelligence cooperation. It consists of a collaboration between government forces and agencies between allies, allowing for both exchange of information as well as practical rehearsals for various security scenarios. Joint exercises are commonly conducted with only close allies such as within NATO or with strategic partners the likes of Australia, South Korea, and Japan due to the inherent intimacy of shared intelligence and command during such activities. Joint training allows for practical collaboration on projects or joint methodologies. For example, developing and testing regional ISR architecture. Countries with greater expertise and experience may share relevant skills and techniques. For example, South Korea is geographically and culturally close to North Korea, a security threat and a key Chinese ally can offer vital input in intelligence on the Korean peninsula. Furthermore, such collaboration allows for standardization of procedures and responses, that are critical in certain intelligence contexts, such as earlier discussed ISR where collected data has to be analyzed and disseminated among allies (Aldrich, n.d.).

Joint exercises have historically been part of the U.S. strategy for collaboration and deterrent. In recent years, the U.S. military is ramping up its training with partner nations such as South Korea, Australia, Japan, and Taiwan. It is an aggressive show of force but does not constitute a conflict, but rather a response to China conducting similar exercises and flexing its forces beyond its sovereign territorial waters. A report from the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command in April 2020 asks U.S. Congress up to $20.1 billion of additional funding specifically for equipment, defensive investments, and military exercises in the region. These funds are aimed at exercises with allies and new intelligence-sharing centers that are meant to improve the U.S. military’s capabilities in deterring the PLA (Barnes, 2020).

As the world is plunged into uncertainty due to the COVID-19 pandemic, tensions between China and the United States are expected to grow because of the origins of the virus as well as China taking advantage of the changing status quo in the world. There are significant calls from experts to fund deterrence initiatives in the form of joint training and international collaboration in the Western Pacific akin to measures placed in Europe against Russia after 2014. The additional funds will serve to create intelligence facilities around Western Pacific and set up military capabilities in the forms of logistics and equipment necessary to train and maintain allied forces to serve as a deterrent for China (Barnes, 2020).

Fostering Effective Foreign Intelligence Partnerships

As China consolidates its hold in the South China Sea, taking control of both natural and artificial islands, many smaller nations in the region are feeling the pressure of tremendous military, economic, and diplomatic leverage of China. Many of these islands are in disputed territory or territorial waters that countries such as South Korea, Taiwan, Indonesia, and the Philippines view as a violation of their sovereignty. However, due to the inability to stand up to China, countries are forced to accede to Beijing’s demands. Many experts feel that it will justify China’s further expansion and eventually an attack on its ultimate objective of Taiwan that China views as its territory (Chellaney, 2018).

Meanwhile, the United States, although recognizing the security threats of Chinese expansion has demonstrated inaction under successive administrations, gradually allowing China to gain control over the strategic South China Sea. Furthermore, there is a lack of clarity regarding diplomatic protocols such as the 1951 Defense Treaty with Manila or the U.S.-Japan Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security, with the U.S. not officially stating whether it would interfere and protect these countries in case of a Chinese attack on their territory or troops. The U.S. response has been muted, focusing on simply safeguarding freedom of navigation in the region (Chellaney, 2018). This has created a divide and potential for weakening trust among partner nations and allies in the region. It will likely impact productive intelligence operations and joint exercises moving forward that are detrimental to contingency plans of deterring China. Without significant input from the United States, the necessary trust cannot be established to foster effective foreign intelligence partnerships.

Expanding Counterintelligence Operations

One of the most rapidly growing and critical threats to national security and USINDOPACOM operations is Chinese intelligence collection operations. Alongside its rapid military development, China has expanded espionage activities through both cyber and human (HUMINT) infiltration of U.S. national security networks, organizations, and vital infrastructure. As Chinese espionage operations have increased significantly, it compromises military and civil capabilities and defense of the United States and its partner countries, requiring an expansion in counterintelligence operations to deter these threats.

Detecting Espionage Activity

Chinese espionage activity is multifaceted and incredibly complex, making it difficult to detect and deter. First, it is necessary to consider cyberespionage. Chinese cybersecurity experts and hackers are one of the most skilled and prolific in the world. It is well known that campaigns originating in China consistently target U.S. infrastructure and servers, including highly sensitive information from government contractors as well as national infrastructure the likes of electric grids. Malicious cyber activity is a key element of modern warfare and can drag the countries into an arms race or potentially military conflict (Jinghua, 2019). Furthermore, China uses traditional human espionage (HUMINT). Although trained Chinese agents operating in the United States and vice-versa, one strategy that China has adopted is approaching vulnerable individuals with access to sensitive projects and information in the widespread network of U.S. government and military contractors. Individuals are offered significant compensation for a small task, usually accepting in desperation, and are then coerced into much more serious and criminal level espionage (Giglio, 2019)

Ironically, both countries are highly dependent on each other’s information technology supply chains. This makes it difficult to defend critical information infrastructure since backdoor access can be established in many networking technologies. Both countries have worked to develop domestic technology industry and capabilities to secure internet infrastructure. From this perspective, the U.S. intelligence, including the counterintelligence department at USINDOPACOM, needs to enhance cyber security capabilities that can withstand cyberattacks, identify origins or intrusions, and keep track of accessed information. Both cyber and human intrusions can be prevented through surveillance of key industries and infrastructure for espionage threats. Proactive investigations into potential or suspicious foreign spy activity can identify threats early on. Finally, it is necessary for collaboration of U.S. intelligence agencies both within the civil sector and military, as well as strong vetting and surveillance of government partners that reduce risks and insider threats (Olson, 2019). Since the U.S. is unlikely to transition to a centralized system of government and military development or production, its reliance and vulnerability on external government contractors must be addressed.

Enhancing Security

Enhancing security efforts focus on coordinated activity and enhancement of surveillance and cybersecurity capabilities. Improving the physical and cyber security of military and civil infrastructure to prevent intrusions. It may be viable to maintain close control of information flow and intelligence exchange as well as identify early on individuals who may be approached by Chinese agents for HUMINT purposes. Taking a more rigorous approach to security clearance and prevention is vital to the human factor of counterespionage activities. This approach has been shown to work as individuals approached by Chinese intelligence involve law enforcement, allowing to set up counterespionage operations (Giglio, 2019). However, the primary objective of enhancing security is focused on cyberspace. The Obama administration has taken significant steps in increasing cybersecurity measures and standard requirements for information systems in government federal agencies, DOD, and contractors. Foreign produced hardware and network technologies should be avoided if possible, in working with any type of sensitive information, both in military and civil sectors of the DOD. Furthermore, there have been several initiatives to accelerate the development of agile cyber capabilities, utilizing a wide range of digital instruments for determent of cyber activity that is targeted at both national security and commercial interests (Department of Defense, 2018).

Dismantling Chinese Espionage Efforts

Dismantling Chinese espionage efforts holds numerous challenges due to the skill and unorthodox methods Chinese intelligence uses. Increasing surveillance and investigating activity discussed earlier is a key step. This is supplemented by increased investigations of Chinese commercial espionage that is targeted at exporting technologies. FBI and DOJ investigations and prosecutions of espionage cases domestically may serve as a deterrent for American citizens to engage in suspicious activity with the Chinese. Finally, it is necessary to foster coordination and unity within the U.S. intelligence community since the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI), meant for oversight of the broader intelligence efforts, lacks authority and influences to coordinate intelligence efforts on an integrated response to Chinese espionage (USCC, 2016).

The U.S. Indo-Pacific Command

The U.S. Indo-Pacific Command (USINDOPACOM) is faced with significant intellectual challenges as the Chinese forces modernize, employ cyber warfare, and maintain the anti-access strategy on all fronts. USINDOPACOM must undergo intelligence augmentation. Recently a large-scale contract was signed with AECOM for a One Acquisition Solution Integrated Services (OASIS) that will develop Innovation and Experimentation Support Services (IPIESS). This will support critical military support aspects of planning, logistics, operations, and resiliency efforts. Furthermore, it will focus on innovation in the fields of sensor enhancement, integration of air, surface, and subsurface analysis capabilities, energy resilience, cybersecurity, artificial intelligence, and electromagnetic spectrum operations (Blinde, 2019).

These efforts are vital in the context of Chinese military and espionage activity build-up. As mentioned briefly during the ISR discussion, the USINDOPACOM lacks the tools and resources to collect and then analyze the intelligence information in full to enhance decision-making. Furthermore, both the unified architecture and cyber security technologies will help counter cyber espionage activities described in this section. Failing to invest and focus on intelligence augmentation will result in the Chinese military eventually elapsing the United States military in various aspects of intelligence capabilities, including sensor blocking, cybersecurity, and being able to potentially hack into USINDOPACOM systems. This is dangerous and can compromise intelligence and military operations efforts significantly, providing China free reign in the region.

Conclusion

China’s expansion in the South Indochina and Western Pacific region in recent years is alarming to the United States and its allies. China is seeking to achieve regional hegemony and its political goals of the reunification of Taiwan. Beijing is using all available tools and leverages of power to achieve its goals. Deploying forces on all fronts, including military, navy, cyberwarfare, and espionage, China is redefining regional power roles and violating rules-based international order. China creates an all-encompassing threat to the national security of the United States in the South Indo-China region and domestically, requiring significant intelligence efforts to recognize and address the tactical and strategic threats through strategies including the use of ISRs, foreign intelligence partnerships, and counterespionage efforts.

In the current status quo, the United States military and intelligence must focus on three aspects of its strategy. Development and deployment of ISRs and regional ISR architecture are critical to have the most current and relevant strategic information about the physical battlefield and content of Chinese forces in the South China Sea, breaking the anti-access barrier when possible. Second, it is important to maintain foreign intelligence partnerships to foster trust and exchange of key information about regional adversaries. Using joint operations and exercises, the United States can both draw from the numerous benefits of foreign intelligence partnerships as well as publicly demonstrate unity and flex of force potentially serving as a deterrent to China. Finally, U.S. intelligence must strongly invest in counterespionage activities against China which has deployed highly evasive and unorthodox methods of espionage along with empowering its cyberespionage activities. It is a vital element of maintaining national security and various sensitive information regarding technologies, methods, or locations of U.S. military and intelligence operations. In combination, information and recommendations offered in this contingency intelligence augmentation plan provide a comprehensive overview of addressing the Chinese threat in the Western Pacific.

References

Aldrich, R. J. (n.d.). International intelligence cooperation in practice. Web.

Barnes, J. E. (2020). U.S. military seeks more funding for Pacific region after pandemic. The New York Times. Web.

Blinde, L. (2019). AECOM awarded US Indo-Pacific Command innovation support contract. Web.

Chellaney, B. (2018). China expands its control in South China Sea. The Japan Times. Web.

Ciovacco, C. (2019). Understanding the China threat. The National Interest. Web.

Department of Defense. (2018). Cyber strategy 2018. Web.

DeVine, M. E. (2019). United States foreign intelligence relationships: Background, policy and legal authorities, risks, benefits (CRS Report R45720). Congressional Research Service. Web.

Doerry, A.W. (2006). Comments on airborne ISR radar utilization. Web.

Giglio, M. (2019). China’s spies are on the offensive. The Atlantic. Web.

Jinghua, L. (2019). What are China’s cyber capabilities and intentions? Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Web.

McGruddy, J. (2013). Multilateral Intelligence Collaboration and International Oversight. Journal of Strategic Security, 6(3), 214-220. Web.

McKenzie, A., & Skiba, J. (2016). U.S. Influence in the Asia-Pacific: An Uncertain Future? Pacific Council on International Policy. Web.

National Research Council. (2006). C4ISR for future naval strike groups. The National Academies Press. Web.

Olson, J. M. (2019). To catch a spy: The art of counterintelligence. Georgetown University Press

Rosenbach, E., & Peritz, A.J. (2009). Intelligence and international cooperation. Web.

Ryan, M., & Sonne, P. (2019). China’s advances seen to pose increasing threat to American military dominance. The Washington Post. Web.

Torelli, A. (2013). US intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance challenges in the Asia-Pacific (Working Paper 37). Retrieved from Royal Australian Air Force Air Power Development Centre. Web.

USCC. (2016). 2016 annual report to Congress. Web.