Statement of the Problem

War environments are understandably harsh work zones. Subsequently, military personnel is exposed to horrendous work conditions that leave them psychologically or physiologically injured and reliant on long-term care. Many military veterans discharged from duty after work accidents qualify for reparations as outlined by the Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) (Maynard & Nelson, 2020). This restitution primarily covers veterans’ healthcare and daily living expenses. However, Maynard and Nelson (2020) further indicate that there is obscured eligibility for veterans’ compensation programs based on an extensive examination of the impairment incurred by a service member and how this disability hinders their earning potential. It is rather unclear how older veterans re-adjust to civilian life and survives after not qualifying for these service-connected disability reparations. This case adopts an evaluation strategy of the service-connected disability program for veterans in the Hudson Valley in the United States.

The apparent problem, thus, is the lack of service connection for aging veterans living in the Hudson Valley, USA. Kane et al. (2012) outline that service connection refers to the disability benefits eligibility for US military veterans under the US Veterans Affairs office for injuries or impairment acquired or aggravated during the course of active duty in the military. Therefore, the program is available solely to veterans whose existing medical conditions were directly caused by their active duty or conditions unique to military service. However, there is relative obscurity in the qualification criteria for veterans, especially with respect to the timeframe for benefits, the mental and financial strain of the application process, and the appeal process if the initial application is denied. To further contextualize the issue, Maynard and Nelson (2020) indicate that, in 2018, approximately 4.7 million veterans were eligible for compensation from the program, with expenditures of $78 billion. Despite these figures, many individuals are excluded from compensation, which is a highly frustrating outcome as they try to navigate their reintegration into society.

Review of Extant Literature

Sustained exposure to violent situations – such as those prevalent in war – can significantly and adversely impact someone’s mental well-being. The United States military recognizes that war has considerable impacts on its members’ physiological and psychological health, which led to the creation of a service connection program. According to Landes et al. (2021), veterans with service-connected disabilities are evaluated by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to be disabled by an injury or illness that occurred or was aggravated during active military service. This intervention is only intended to benefit people exposed to conditions that left them mentally or physically impaired while in service. Therefore, an accident that occurred while in the military, even if not during deployment, is considered a condition that qualifies as a service-connected disability.

The government has been providing benefits to the veterans in varying degrees since the colonial settlements of America. Panangala et al. (2014) observed that in 1718, Rhode Island created legislation that offered benefits to every soldier, officer, or sailor who served in the armed services and the family members or dependents of those who perished during the war. Such legislation has undergone many changes over the years. In 1776, Continental Congress argued that disabled veterans should receive half of their monthly payment for as long as their disabilities existed (Panangala et al., 2014). The advancement in research and medicine indicated that resulting disability from military service is not readily apparent. Therefore, from the 1920s through to 2008, Congress examined conditions that might qualify as veterans’ disabilities or illnesses caused or aggravated by being in military service, culminating in a comprehensive report that helps in the decision-making process (Barnes et al., 2007; Bodurow & Samet, 2008; Panangala et al., 2014). The conditions made it easier for deserving veterans to receive necessary compensation and help in their time of need.

Military spending in the US has been a significant aspect of budgetary allocations. This results in a rapidly-expanding military force – one of the largest in the world – and an equally extensive veteran affairs department (Stern, 2017). The size of the military grew exponentially after the 9/11 attacks, when the then president of the US, George W. Bush, declared a ‘Global War on Terror. Overall, medical discharge is only one among many honorable cessations of military service for personnel. Stern (2017) indicates that depending on the severity of the injury, which is determined by a number of psychological, medical, and functional assessments, it determines whether a physical and/or psychological condition will interfere with a service person’s ability to perform their active military duties. No specific list of medical conditions may lead to a medical discharge, hence standardization of approaches. Still, these injuries may include but are not limited to extremity impairments and amputations, paralysis, bullet and shrapnel wounds, severe burns, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), spinal cord and brain injuries, nerve damage, and the loss of vision or hearing (Stern, 2017). The service-connected disability program of the VA was specifically designed to aid in the reintegration of such medically-discharged veterans whose injuries render them unable to join and be productive in the civilian workplace.

The program is essential because it provides long-term care benefits to veterans. As Redd et al. (2020) described, physical and mental injuries, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), are major comorbidity for veterans. As a result, focusing on care plans that offer solutions to the illnesses that occurred or were exacerbated while serving in the military reduces the burden on the veterans and their families. Spinola et al. (2021) indicated that medical or psychological evaluations are performed to determine eligibility for service-connected disability benefits. Therefore, this evaluation process incorporates medical records detailing a veteran’s history before and after discharge, including collateral reports and neuropsychological exams. The evaluations are integral to the program because it determines the monthly stipend and other benefits, such as qualifications for Veterans Healthcare Administration service, survivor benefits, and preferential hiring for federal jobs (Spinola et al., 2021). Evaluating the veterans’ eligibility is lengthy, and individuals must fulfill certain conditions.

The implementation of the service-connected disability program for the VA is also plagued with structural and systemic issues. The biggest hurdle to qualification for veterans is arguably establishing the linkage between their injury(s) and their service record to meet the central eligibility standard for the program (Fried et al., 2018). This makes intuitive sense. For instance, linking a veteran’s delayed-onset posttraumatic stress with their military service could be difficult and supported solely by speculation. Fried et al. (2018) provide one such example in the case of Vietnam veterans exposed to over 20 million gallons of a US-administered ‘Agent Orange,’ a tainted herbicide contaminated with dioxin. The researchers estimated that approximately 2.7 million US military personnel had been exposed to Agent Orange during their deployment (Fried et al., 2018). Despite this, a very small proportion of these individuals were actually eligible for the Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) service-connected disability compensation, as they could not demonstrate a nexus between their diagnosed conditions and military service – an element of eligibility that the VA refers to as ‘presumed service-connected diagnosis (Fried et al., 2018). Therefore, eligibility criteria for the VA service-connected disability program are rather exclusionary, and necessary reform and intervention is needed to address the glaring deficits that lead to the omission of otherwise-deserving military veterans.

Description of the Program to be Evaluated

The problem identified in this case is the lack of Service Connection among the aging veterans living in the Hudson Valley. Service Connection refers to US Veterans Affairs disability benefits eligibility for the injuries or impairment acquired during or aggravated by military service (Kane et al., 2021). Therefore, this crucial program is only available to veterans whose medical conditions were directly caused by the military service or the conditions exposed to the members while in the military. In 2018, the number of veterans who qualified to access remuneration was 4.7 million, and the total expenditure in the year was $78 billion (Maynard & Nelson, 2020). Consequently, most individuals are excluded from the compensation list, which frustrates them as they navigate through challenges experienced during their reintegration into civil society. The service-connected members enjoy a wide range of benefits, such as supported work settings, residential services for veterans with mental conditions, and inpatient and outpatient services (Maynard & Nelson, 2020). The treatments are catered for by the government based on the eligibility percentage, and reimbursement provides a significant income to those whose earning capacity has been reduced.

While this program is beneficial to the veterans in the service-connected listing, other former service members are neglected by the government. Specifically, there is an estimate that individuals eligible for Service Connection will increase to over 5.6 million and raise expenditure to $129 billion by the year 2028 (Maynard & Nelson, 2020). This sharp increase in program dependents will strain the financial budget set aside to help the veterans. Therefore, Morgan et al. (2020) proposed reducing barriers to accessing these programs by tangible components such as cash, scholarship, social amenities, and healthcare facilities. For some veterans, especially mentally ill and older adults, this compensation is the only source of income. As a result, there is a need to expand eligibility to cover some of the cases ignored by the qualification criteria.

Theory of Change Model

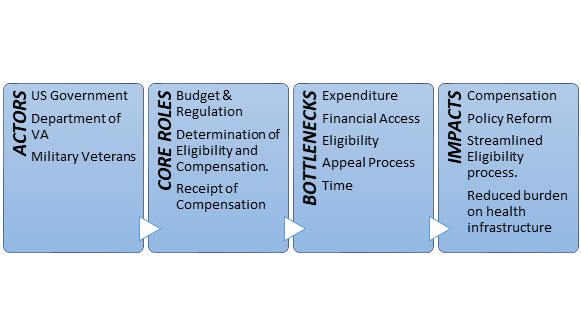

Figure 1 below outlines the theory of change model adopted for this program evaluation. As Grinnell et al. (2019) indicate, the theory of change model is indicative of implicit knowledge of the program, which in this case is a succinct appreciation of the actors involved in implementing a federal and provincial veteran’s service-connected disability program, the roles of the respective actors, the problems identified in the review of extant literature, and finally the impacts that the proposed intervention would precipitate.

The focus of the Evaluation

The US has arguably one of the most exhaustive assistance systems for war veterans worldwide. This system’s genesis can be traced to 1636, during the war between Pequot Indians and the Pilgrims of Plymouth Colony (VA Office, 2022). The Pilgrims passed legislation that mandated the support of disabled soldiers by the colony. The Continental Congress of 1776 later began championing enlistments amidst the Revolutionary War, availing pensions to soldiers injured at war. Single states and communities helped veterans by providing them with direct hospital and medical care in the Republic’s early days. However, the federal government licensed the first medical facility and domiciliary for veterans in 1811 (VA Office, 2022). Additionally, the county’s veteran’s assistance program was boosted to include pensions and benefits for veterans as well as their widows and dependents. This implementation has undergone numerous iterations and policy revisions to become the Department of Veteran Affairs service-connected disability program as it exists now.

For an individual to fit the client profile of VA service-connected disability compensation, they must fit certain criteria. First, they should have actively served or been on either inactive or active duty for military training. As for an individual on inactive duty, only a disability emerging from a stroke, injury, or heart attack will qualify for compensation. Second, a specific event during one’s service in the military must have contributed to or caused a medical condition, and one must provide proof of the said event. Third, an individual must have a qualifying medical condition that inhibits their capacity to sustain meaningful, gainful work. Fourth, a VA must rate one’s medical condition to at least 10% disabling (VA Office, 2022). That is, although an individual might be eligible for other VA benefits, they will be unable to access disability compensation if their disability is rated at less than 10%. Lastly, an individual’s medical condition should not result from their willful misconduct or what the VA terms as an act that involves conscious wrongdoing or a known prohibited action.

In order to be eligible to be a staff member of the VA in the US, being a US citizen is mandatory unless for Title 38 and Hybrid Title 38 roles. An individual can apply for any position that meets both the selective factors and minimum qualifications required. Depending on the role, the qualifications needed may include competency in English, graduate of an accredited/approved program, or a current unrestricted, active, and full professional license from any territory, commonwealth, or state of the US or from the District of Columbia (VA Office, 2022). The VA offers different types of benefits to the veterans eligible to receive disability compensation. These may include pensions, grants, and compensations for veterans with service-connected disabilities. In most cases, VA offers healthcare programs to veterans, vocational rehabilitation and employment, specially adapted housing grants, service-disabled veteran insurance, annual clothing allowance, and concurrent retirement and disability payments.

There are generally low satisfaction levels among the VA service-connected disability program stakeholders. Stakeholders in this sense include the federal government, VA staff, war veterans, and their dependents. There are increasing budgetary expenses that place considerable strain on government funding of the VA program. Conversely, an obscure and long qualification criterion excludes many military veterans from accessing the service-connected disability compensation they rightly deserve. The opaqueness in the eligibility criteria, primarily the difficulty in proving the nexus between military injuries and their service record, is outlined in extant literature (see Fried et al., 2018; Stein, 2017).

Possible Data and Measures

The establishment of a sustained solution for the identified program deficiencies and availing help for the veterans requires a multidimensional solution. Veterans experience a host of issues as they transition into civilian life, and several remedies could be implemented to help their reintegration. For medically-discharged service members, the VA provides a non-exhaustive list of medical conditions and injuries that may result in this outcome, including physical, psychological and functional impairments, and a number of remedies are implemented to help discharged service members – including the VA service-connected disability compensation program.

In a federal scope of review, the VA’s database on service-connected disability benefits, called the Veterans Service Network Corporate Mini Master File (VETSNET), has immense utility to program designers and researchers. The database is the primary source of information regarding VA benefits and links identification markers to clinical data and discharge records (see Fried et al., 2018). However, the shortcomings of this approach for this intervention program would be twofold. The first is that the scope of this evaluation is highly limited to the VA service-connected disability compensation program in the Hudson Valley, USA, rather than a federal level. This limitation of scope, while it allows for a highly specific intervention approach, also renders the VA database null due to the records lacking that level of filtration (Fried et al., 2018). The second limitation is that veterans included in the database are individuals who have already qualified for the service-based disability compensation program. This makes use of this approach counter-intuitive as eligibility into the program is a problem outlined by this program.

Therefore, this evaluation prefers to conduct asset mapping of the available community assets and resources for elderly veterans within the Hudson Valley region. Asset mapping allows for a near-continuous appraisal of the necessary societal resources, including residents with the skill and expertise to help, voluntary clubs and networks, economic and physical assets, and local private and public institutions (Allar et al., 2017). As per this description, the Hudson Valley has extensive resources to help aging veterans, including 12 VA medical centers, 48 outpatient clinics and 16 Veteran centers specializing in readjustment counseling, as indicated by NYS Health Foundation (2017). These resources provide direct forms of intervention to offer healthcare services to veterans and address the more immediate medical concerns of aging veterans. Regional medical and social programs allow local administration to address the deficiencies that the VA’s exclusionary eligibility criteria do not, pending extensive policy reforms that expand qualification into the service-connected disability compensation program for veterans.

Possible Findings and Lessons Learned

An ideal outcome of the VA service-connected disability program would be to afford all eligible disabled war veterans the compensation they are owed. This can only be possible if the stringent measures around accessing compensation are loosened to allow anyone well-qualified to earn their dues. Additionally, measures should be put in place to cater to those who contracted medical conditions well after their service, especially when those conditions directly result from their past military duties. VA staff should also endeavor to seek ways in which they would hasten the compensation application and payment processes. By either employing more personnel or simply accelerating the due diligence required for a veteran to access their compensation, the VA would minimize the physical, mental, and financial strain put on them.

One of the measures of accountability for the VA service-connected program would be an explicit increase in the number of war veterans- with debilitating medical conditions such that they cannot get gainful employment- in their payment plan. Additionally, there should be extended psychiatric help to veterans who may be ineligible for compensation but struggle with mental illnesses after service. There should also be forums put in place for all veterans, regardless of their eligibility status, to access some basic forms of upkeep and benefits for their valiant roles in serving their country. There are numerous evidence-based interventions that have shown a clear positive client change. One such intervention is integrating technology in several VA Hudson Valley utilities to help minimize travel while still availing essential services to veterans. These modifications have allowed veterans to securely set up remote visits and transmit health data to experts based in VA centers. By doing this, most veterans- including those not eligible for Service Connection- can access the basic and complex medical care they need at the press of a button.

References

Fried, D. A., Rajan, M., Tseng, C. L., & Helmer, D. (2018). Impact of presumed service-connected diagnosis on the Department of Veterans Affairs healthcare utilization patterns of Vietnam-Theater veterans: A cross-sectional study. Medicine, 97(19), 1-8. Web.

NYS Health Foundation. (2017). Veterans and health in New York State. Web.

Maynard, C., & Nelson, K. (2020). Compensation for veterans with service-connected disabilities: Current findings and future implications. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 31(1), 57-62. Web.

Spinola, S., Fenton, B. T., Meshberg-Cohen, S., Black, A. C., & Rosen, M. I. (2021). Comparison of attitudes towards the service connection claims process among veterans filing for PTSD and veterans filing for musculoskeletal disorders. Medicine, 100(35). Web.

Redd, A. M., Gundlapalli, A. V., Suo, Y., Pettey, W. B., Brignone, E., Chin, D. L., Walker, L. E., Poltavskiy, E. A., Janak, J. C., Howard, J. T., Sosnov, J. A., & Stewart, I. J. (2020). Exploring disparities in awarding VA service-connected disability for posttraumatic stress disorder for active duty military service members from recent conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. Military Medicine, 185(Supplement_1), 296-302. Web.

Kane, N. S., Anastasides, N., Litke, D. R., Helmer, D. A., Hunt, S. C., Quigley, K. S., Pigeon, W. R., & McAndrew, L. M. (2021). Under-recognition of medically unexplained symptom conditions among US veterans with Gulf War illness. Plos One, 16(12). Web.

Panangala, S. V., Shedd, D. T., Moulta-Ali, U. (2014). Veterans Affairs: Presumptive service connection and disability compensation. Congressional Research Service. DIANE Publishing.

Barnes, D. K., McCutchen, S. R., Ford, M. A., & McGeary, M. (Eds.). (2007). A 21st century system for evaluating veterans for disability benefits. National Academies Press.

Landes, S. D., London, A. S., & Wilmoth, J. M. (2021). Service-connected disability and the veteran mortality disadvantage. Armed Forces & Society, 47(3), 457-479. Web.

Bodurow, C. C., & Samet, J. M. (Eds.). (2008). Improving the presumptive disability decision-making process for veterans. National Academies Press.

Grinnell, R. M., Gabor, P., & Unrau, Y. A. (2019). Program evaluation for social workers: Foundations of evidence-based programs. Oxford University Press, USA.

VA Office (2022). Veterans Affairs. Web.

Stern, L. (2017). Post 9/11 veterans with service-connected disabilities and their transition to the civilian workforce: A review of the literature. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 19(1), 66-77. Web.