Introduction

Human civilization is changeable and impermanent: the evolution of social thought, combined with adequate scientific and technological progress, provokes qualitative changes in the world order. Centuries ago, global wars and violent conflicts were natural and even revered instruments for resolving differences. Trying to free themselves from the oppression of political games, warlords conquered the territories and wealth of other countries by force and brutality. This is easily borne out by a critical appraisal of most of the famous historical figures of the ancient world. Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, Hannibal, Charlemagne, Genghis Khan, and even Joan of Arc: each of these widely known figures of history was involved in warfare and thus associated with brutality. In such scenarios, central states and empires rarely sought to become each other’s friends but instead sought to expand their influence across the planet selfishly.

Meanwhile, progress continues to rule the world, and many changes have passed since the last medieval wars. States, recognizing the economic benefits of cooperation, began to form alliances that made sense even during world wars. Closer, fraternal ties began to form between certain states, allowing for reliable economic-political alliances. In addition, military engineering progress also metamorphosed. Along with the development of science, the armaments of the countries appeared potent and unique weapons, which horrified all sides at the same time. In particular, it is talking about nuclear bombs, the use of which in the modern world is tantamount to the killing of all humanity.

However, many states, even now, and especially during the Cold War, actively stockpiled nuclear weapons as an instrument of intimidation of political opponents. The modern reader may be convinced that no developed state with weapons of this magnitude in its arsenal would use them since the consequences of such an explosion would be irreversible. However, the fact that states do not abandon nuclear weapons altogether means only that their existence characterizes a country as strong and ready to respond in the event of a military offensive. To put it another way, nuclear weapons are used as a measure of last resort in geopolitical discussions.

Although it seems evident that nuclear weapons on a planetary scale will hardly ever be used, the question of some countries having such a tool seems very sensitive. This research paper explores the potential of nuclear weapons as a method of creating international peace and preventing violent wars between states. It is a helpful summary of contemporary public discussion and debate, supported by scholarly sources and statistical findings. The overall thesis of the entire research paper is that the use of nuclear weapons is indeed a tool of deterrence, although this influence may gradually cease to be relevant.

History of Nuclear Weapons

One of the overriding areas of human thought that accurately reflects the need for creativity, creation, and creation is science. Science is the most excellent tool of civilization, which allows us to optimize life through incredible discoveries created systematically. It is no secret that it is thanks to scientific thought that modern communities have all the economic, technical, and even social benefits they have. It is essential to understand. However, that science does not exist separately from its authors: science is only a tool that allows, using known laws, formulas, and identities, the creation of new discoveries. Consequently, it is critically important to recognize the functional role of science as a response to the social demand being created.

There was no science in the classical sense of science in primitive communities since ancient people hunted, built houses, and improved tools and agricultural skills. It cannot be called exact science because terminologically, there is probably lacked critical thinking, hypotheses, and prediction: it might be like a young child intuitively exploring the world (Flom). However, this does not mean that people did not engage in the same activity that science does today, namely, the attempt to know reality objectively. Given the functional role of scientific discovery, it is safe to say that primitive people were scientists of their time, studying the arts of building, hunting, and warfare. This solved their primary task: the need to survive in difficult times.

With the emergence of rational thought, however, scientific ideas began to emerge as well. With the basic skills of mathematics, philosophy, and the natural sciences, the people of the new age sought to integrate them in order to make new discoveries. It was during the late Middle Ages that the progress of military technology became particularly noticeable when armor and iron swords were replaced by firearms, cannons, and crossbows (Cronin 73). Science was once again called upon to solve societal problems relevant to the times.

A series of scientific discoveries, already harder to connect with domestic needs, were made in the last two centuries. The experiments of Rutherford, the Curies, and the discovery of Becquerel and Einstein allowed humankind to delve into the microcosm by studying the structure of atoms and some of their properties (“100 Incredible Years of Physics”). The apogee of this study for military technology is the creation of the nuclear bomb as an applied response by military leaders to the discoveries of the scientific world. Nuclear weapons are still considered one of humanity’s ingenious inventions, managing to integrate the objective laws of the atomic world with quite measurable tasks of national importance.

The answer to the question of who is considered the founding father of nuclear weapons cannot be unequivocal. On the one hand, each country tries to assert its primacy in the history of nuclear weapons: the American Robert Oppenheimer, the Soviet scientist Igor Kurchatov, and the French physicist Frederic Joliot-Curie (Karaganov 102) is named founders. Although each of them has made an indisputable contribution to this type of weapon, in reality, there can be no single ancestor of the nuclear bomb since its history begins long before the actual patent for the bomb. It is quite correct to place the benchmark in the history of nuclear weapons in 1896 when French physicist Antoine Henri Becquerel accidentally discovered the property of radioactivity. In modern science, radioactivity refers to the ability of unstable nuclei to transform into other nuclei by emitting quanta of elementary particles. It is these quanta (portions) that are the most powerful doses of energy that result from nuclear decay in a bomb.

After 1896, the scientific community became radically interested in radioactivity. History knows sad examples of the deaths of great discoverers who were unfamiliar with the murderous effects of radiation and, because of this, became victims of forces beyond human control (Watts). After Becquerel, the world saw the laws of radioactive decay, the properties of alpha, beta, and gamma radiation, theories of nuclear isomerism, and the abilities of certain isotopes of classical atoms to be radioactive. All this led to the fact that in 1938, on the eve of the European war effort, the German scientist’s Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann were able to prove the ability of uranium nuclei to fission artificially (“100 Incredible Years of Physics”). In other words, humanity at the time obtained a terrifying power: to cause nuclear decay accompanied by the release of megatons of powerful energy.

Hitler’s Germany as Catalyst for Nuclear War

By the end of the 1930s, Adolf Hitler, the central figure of German National Socialism and the flamboyant leader of the Fascist movement, had a unique political influence that extended beyond Germany. Having managed to build a powerful state machine based on ethnocentrism and the promotion of genocide and brutality, Hitler declared war on the world in 1939, starting with Poland. Without going into the history of World War II, as it is not a subject of the current study, a transparent parallel should be drawn between Hitler’s offensive and the beginning of the German nuclear program. Seeing the potential in the discovery of Hahn and Strassmann, Adolf formed a ban on the export of uranium from the country in 1939, which is understandably seen as a concentration of research forces to build the first nuclear bomb. The leading scientific figure and leader of the German classified nuclear bomb project were Werner Heisenberg, who by that time had a firm academic reputation as a Nobel Prize winner in physics.

During the first years of World War II, the German group was actively developing a nuclear reactor, solving the issues of saturation of uranium-235 with the radioactive isotope and the search for initiators of a dramatic release of energy. It was not until 1942 that Heisenberg and Döpel succeeded in building a prototype reactor, which, however, was not ideal, leading to the world’s first nuclear accident. When German scientists were close to building a second, efficient reactor that could reach a critical point and thus give Hitler an unbeatable weapon, foreign troops entered Germany, and the reactor was taken to the United States (Popp 10). Thus, the scientific theater of nuclear bomb production moved across the Atlantic Ocean.

It is true that the American nuclear project (“Manhattan Project”) was conducted parallel to the German one with the help of Albert Einstein, who had emigrated from Nazi Germany. The war was a catalyst for the accelerated development of nuclear weapons, but the reasons for this will never be known. On the one hand, the leaders of the country might not have suspected how powerful an explosion from a nuclear bomb would be, so they might indeed have wanted to use it in action. On the other hand, seeing the military competition and pressure from the Japanese, the Americans may have wanted to develop the strongest weapon first as possible leverage. Research in the U.S. was not as strict and rigid as it was under Hitler’s totalitarian regime, which is probably why by 1945, the Americans were able to create the first three versions of working nuclear bombs. This allowed the Americans to show the world what kind of weapons they now had.

Subsequent episodes of the military history of nuclear weapons are known to all. The Americans, having confronted Japan as a country allied with Hitler’s Germany, launched two nuclear strikes against the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6, 1945 (Popp 9). The total number of casualties does not appear to be accurately measured, but according to rough estimates, the number of killed inhabitants of the two cities exceeded two hundred thousand. This was the first case in human history of the violent and deliberate use of nuclear weapons for military purposes. Obviously, the world community did not encourage such actions since the destructive effect of a nuclear bomb, even for military purposes, appears to be excessive. Subsequent chapters of history have therefore sought to recognize prohibitions on the use of nuclear weapons and worldwide disarmament.

Thus, in summarizing the brief history of military nuclear weapons, it must be said that they were developed in response to government requests. Although the use of nuclear energy transcends only violent tasks, it is in the military sense that nuclear weapons are the most dangerous instrument. Since the end of World War II, the world community has initiated the signing of many international instruments urging states to renounce the use of nuclear weapons for non-scientific purposes. So far, such agreements and an adequate assessment of the geopolitical agenda, in addition to the absence of serious international conflicts, have prevented the world from nuclear catastrophe.

Nuclear Deterrence

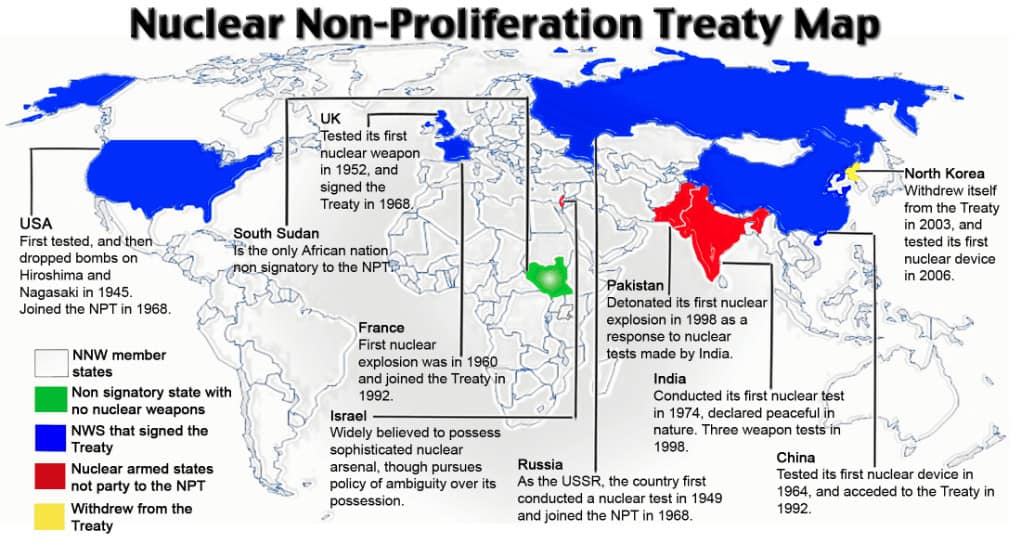

When the use of nuclear weapons for military purposes became an obvious problem for achieving international peace, disarmament acts and agreements were enacted to compel countries to renounce the use of such weapons. One of the fundamental covenants is the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), initiated by the U.N. and signed by a host of member states on July 1, 1968 (Pelopidas 491). The NPT imposes many restrictions on the use, storage, and proliferation of nuclear weapons by its parties. In addition, one important consequence of the NPT is the classification of countries according to their possession of nuclear weapons, as shown in Appendix A. Thus, only those states that conducted at least one nuclear test before January 1, 1967, can be called possessors of nuclear weapons. These traditionally include the United States, the Soviet Union (Russia), China, France, and the United Kingdom. India, Pakistan, and North Korea, all of whom have declared nuclear weapons but have not been or are no longer parties to the NPT, were later added to this list.

The eight countries described above are distinguished by Israel, which has a policy of non-transparent nuclear deterrence. With respect to Israel, it is known that it is not a party to the NPT, but there is no proven fact of possession of nuclear weapons in the country. There are rumors that Israel has developed weapons that, among other things, can be transportable and thus have clear military advantages, but the Israeli authorities do not officially confirm this data. This creates an ambiguity that is extremely advantageous to Israel: in fact, having no obligations to the international community, the authorities of the country may not report on the existence of nuclear weapons. On the other hand, many of Israel’s enemy countries are wary of direct military clashes with the Middle Eastern state because of the danger that it might use potentially available nuclear weapons. This, in turn, is often a reason to list Israel as one of the five countries that are certain to possess nuclear weapons.

Because of this, the threat of new nuclear explosions has become less urgent and pressing but has still not been fully resolved. Having a policy of nuclear deterrence is an ambiguous global strategy that has both advantages and disadvantages. On the one hand, the number of countries possessing nuclear weapons has indeed declined, which means that the likelihood of using such an instrument for military purposes has also been minimized. Each of the six countries that possess nuclear weapons is a strong power with a stable political apparatus, which means that the impulsive release of nuclear warheads, as in the case of terrorist states, is virtually ruled out. The concentration of nuclear weapons in some countries thus partially solves the problem of their unwise use. This is a kind of use of the power of the “most responsible” members of the world community, who have the power to solve the problems of nuclear catastrophe.

In turn, it is impossible not to notice the obvious problem of justice and equity that such a concentration of nuclear weapons raises. This situation puts the power over the threat of nuclear war in the hands of only some countries, which certainly raises questions of sovereignty, equality, and justice. In this context, it appears that some countries have supremacy over others, although there were no initial prerequisites for such a distribution.

In an attempt to partially solve this problem, an international nuclear weapons sharing program was created in which the U.S. gave some of its warhead stockpiles to some European countries. By now, some of the donor countries are united in a common NATO alliance that aims to expand the U.S. military presence in Europe. In this sense, it seems unsurprising that the Americans are eager to share their weapons since this would solve two problems at once. Firstly, the United States gets allies in Greece, Britain, Turkey, Belgium, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands (CACNP). Thus, these countries are not expected to oppose the United States militarily. Second, the U.S. does not give its weapons for gratuitous perpetual use but “places” and “stores” them so that they can be used if necessary. This creates a reciprocal threat to Russia (USSR), which is the main nuclear rival of the U.S. Finally, such an action on the part of U.S. authorities can be seen as political generosity since certain European countries have been given great military capabilities and power in conflicts of nuclear significance.

Geopolitical Balance

If one recognizes that there is a direct correlation between the distribution of nuclear weapons and the military power of the powers, the situation does not seem unfair: states that over the past centuries have fought — physically, intellectually, and economically — against each other eventually created a bipolar world system, in which confrontation between the USSR and the United States was the most urgent threat. China and Great Britain, as some of the most developed countries in the world, also take part in this race, which means that one can say that there is some balance of political power between all the countries participating in the NPT.

It is noteworthy that this balance is extremely unstable: any change on one side of the nuclear club directly leads to changes on the opposite end. It is probably for this reason that the silent confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union since the Cold War, which has spread to its successor, Russia, continues to be relevant. Each country’s political and public propaganda continues to portray its adversaries in a negative light, demonstrating the potential for a national threat from the outside. From a domestic policy perspective, such strategies seem understandable, although, in the context of extended globalization, it is naïve to assume that a critically minded national population will take far-fetched threats seriously. In terms of foreign policy, this allows countries to be seen as separate mechanisms, actively connected to the rest of the world but “more so” connected to some of the nuclear club countries. Thus, while acknowledging the undoubtedly complex ties between Russia and China or Russia and Britain, it is impossible to ignore the obvious tension between the United States and Russia. This only further demonstrates that the post-war nuclear balance remains dynamic and vibrant.

An excellent analogy for the described balance is the example of the multifaceted scales, the scales of which are represented by the countries possessing nuclear weapons. Because digitalization makes political communication extremely accessible, any change in one side’s nuclear weapons immediately triggers fluctuations for other countries. For example, the increase in nuclear warheads and news of North Korea’s nuclear tests resonated elsewhere (Sang-Hun). Thus, the geopolitical balance is created on the sensitive build-up of power on these scales.

Moreover, it is for this reason that no country can completely abandon nuclear weapons since no other country can do the same. This is the deterrent power of nuclear weapons that keeps countries in relative equilibrium: the scales continually reach a certain balance. It is important to stress that such reports, as in the case of North Korea, often come from the government apparatus since news about nuclear weapons or methods of defense against them is part of political propaganda. In this sense, the international speeches of Russian politician Vladimir Putin, who frequently informs his foreign counterparts about the military might of the largest European state and the innovative developments that will allow the country to defend itself against nuclear warheads, come especially to mind (CBC News 00:00:09-00:00:24). These speeches emphasize only the possibility of using weapons as a retaliatory strike. Such words, addressed to the world community, are a kind of geopolitical protection for the country: it is as if the president is saying that in case of a nuclear threat, the country will be protected. This practice, however, is true not only for Russia but also for Washington. Former U.S. President Donald Trump also often spoke publicly about America’s nuclear capabilities, and it was under him that initiatives to build up the country’s nuclear capabilities were launched (Axe). To put it another way, with regard to nuclear weapons, the public speeches of key politicians play an important role, even if no real action to change the country’s nuclear agenda takes place.

Interestingly, even if the major powers on the list of five countries decide to abandon nuclear weapons all at once, this would be one of the most dangerous geopolitical decisions. The reason for the threat lies in the fact that there are countries that ambiguously possess nuclear weapons or have them in their arsenal but do not report them. Then military power of this level will become a priority force for such countries, which means there is a risk that the world will be destroyed. Thus, countries find themselves in a certain dependence on nuclear weapons, in which it is challenging to refuse to have them, and this can be detrimental to the development of the international world. In this case, it is obvious to predict that until the world community reaches the point of completely abandoning nuclear weapons, the nuclear capabilities of countries will continue to be built up as an instrument of influence and pressure on competitors.

Nuclear Weapons as an Instrument of Peace

Despite all the problems with which the existence of nuclear weapons is associated, it should be recognized that they can act in part as a catalyst for international peace. To support the above argument, it is a priority to acknowledge the existence of nuclear weapons: each NPT country has its own stockpile of warheads, which means that the risk of using them will never be zero. Whatever the geopolitical conflict, the possibility always remains relevant, and all the consequences flow from it, be it the death of communities, radioactive contamination, or nuclear winter. However, it is precisely these problems that become an option for achieving international peace, albeit one built on mutual fear.

Regarding nuclear weapons, many of their opponents ignore one important fact: Ever since major countries began to wield such power, global military conflicts have ceased to be an issue. In the 76 years since American bombs bombed Japanese cities, not a single major conflict has taken place on the physical plane, with all confrontations and mutual animosities moving into the informational reality. Nuclear weapons have enabled the world to abandon world wars in this way but have not resulted in wars ceasing altogether. Over the past 76 years, local wars, be they Vietnam, Afghanistan, former Yugoslavia, and Israel, have indeed resulted in casualties and physical damage, but their scale is not comparable to the realities of World Wars I and II. Many of these wars have even ceased to be called wars terminologically but instead have been given the status of military conflict.

One can parry this argument by citing the possibility of World War III during the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union, but relations during that period were much more profound. In fact, the threat of nuclear war was talked about in the postwar period and before the 1980s by many media, and it was reflected in academic sources (Colby 25). However, human history makes it clear that war did not take place. One of the most obvious reasons for the absence of nuclear strikes during such a tense bipolar time for the world was the equality of nuclear capabilities between the two adversaries. Each of the politicians understood that even if nuclear warheads were aimed in the direction of their enemy, the same power would at the same time come down as a counter-strike, and thus the efficiency of such a war would be unwarranted.

It is noteworthy that the possibility of achieving international peace may be a consequence of having nuclear weapons for particular countries. In particular, for those powers that are parties to the NPT, it can be assumed that their citizens feel a greater sense of national security because they understand their country’s military might. In turn, a sense of security is an important factor in reducing stress, which affects the nature of international relations. It is certainly naïve to assume that relations between Americans and Brits will be different just because each country has nuclear weapons, but it is not advisable to rule out such causal links until they are disproven.

Nuclear Peace

The theory of nuclear peace, as part of a general theory of international relations, is an important part of achieving peace. In the U.S.-Soviet confrontation, it has already been shown that equality is the cause of deterrence. Thus, an equal distribution of nuclear weapons could make it possible to achieve the conditions for international peace if that is the goal of the world community. Obviously, issues such as accountability, fairness, and equal distribution become relevant in this case. For example, if most of the existing weapons were made in the United States and Russia, would such an equal distribution be in the interest of the powers? Furthermore, the theory of nuclear peace confronts questions of transparency and the absence of corruption in the international governing bodies that are responsible for such a distribution. As the practice of any international organization shows, there is always the threat of fraud and espionage within them, which means that it is not possible to be fully confident in the effectiveness of such a body. Ultimately, even if countries turn out to be bound by international agreements, the possibility of impulsive, emotion-driven use of nuclear weapons for countries whose politicians may not perceive this responsibility can never be ruled out. Moreover, history continues to show examples of military coups in countries. In particular, if there were a base with deployed nuclear weapons in U.S.-controlled Afghanistan, the threat of the Taliban using that arsenal could have been one of the most dangerous events of the year. Thus, a nuclear world may theoretically represent an ideal concept of equal distribution of existing stockpiles, but in practice, this reality faces many nuances.

In this context, it is particularly important to recognize that the fall of nuclear stockpiles into the hands of terrorist communities would be the most serious problem for the global public. While recognizing the absolute unacceptability of such a scenario, accountable NPT states are obliged to ensure full control over a strategically important arsenal; it is possible that sabotage or force majeure could result in such stocks ending up in the hands of non-state aggressive terrorists. One of the first consequences of such a scenario could be the use of acquired weapons against enemy countries, causing a local nuclear war. However, it is clear that a nuclear war cannot be of a local nature, given the long-term consequences of using such bombs. Even if one recalls the examples of Soviet Chornobyl and Japanese Fukushima as civilian uses of nuclear energy, contaminated territories still do not seem possible to settle after so many years. Thus, terrorists who obtain nuclear weapons can use them because they have no threat of retaliation, especially in the case of jihad.

Another, more realistic consequence of such a scenario is an imbalance of geopolitical forces. The acquisition of nuclear warheads by terrorist communities would cause a public outcry, forcing NPT participants to retaliate by either recognizing the terrorist state as sovereign or engaging in military conflict with it. In the second case, the probability of nuclear war again becomes higher.

It is noteworthy that the theory of nuclear peace, constructed in the middle of the last century, does not take into account the technological progressiveness of the world. For today’s geopolitical agenda, digital leaks are not uncommon, especially at government levels. History knows examples of the theft of personal data of presidents and large-scale leaks of classified economic documents (Benner). In this situation, it is fair to acknowledge that information, however hidden, can eventually be compromised through advanced digital hacking networks. By approximating these conclusions, nuclear stockpile information, up to and including remote control of nuclear warheads, can be intercepted by criminals, the consequences of which do not seem favorable to achieving international peace.

Conclusions

The central thesis of this research paper was the belief that the availability of nuclear weapons is a critical factor in deterring global military conflict. In other words, international peace is made possible by the most powerful military weapons ever invented by humankind. This may seem paradoxical, but the main reason for the validity — or relative validity — of this statement is to achieve a balance in the distribution of nuclear weapons among countries. Since the nuclear-weapon-possessing countries, fully aware of all the consequences of a nuclear strike, have equal or equivalent stockpiles, the likelihood of explosions is reduced. This thought is a crucial predictor of international peace.

It is clear from the above words that the concept of “the more, the better” is used for such international peace. An iconic proponent of such an idea is the American political scientist Kenneth Neal Waltz, who believed that an increase in the number of new nuclear states would be a positive factor in deterring nuclear catastrophe (Sukin 1015). There is a solid logic to this assertion, for, under such conditions, the world becomes multipolar, and each of the countries possessing nuclear weapons has the political weight in making key decisions.

However, it is clear that the concept of “the more, the better” may eventually get laid off and lead to surplus problems. If a large number of countries possess nuclear weapons, the likelihood of their use naturally increases. In this case, it is especially appropriate to recall Murphy’s law of philosophy, which says that if something terrible can happen, it will happen. To be sure, using such paradigms in such a responsible matter of planetary importance does not seem serious, but key world events have often happened accidentally, unintentionally. The concept of “less is better” is the opposite of Waltz’s views. American researcher and political scientist Scott Sagan, an advocate of the organizational theory of international relations, believes that the distribution of nuclear weapons to the new nuclear powers could be a destructive measure since such countries may not be willing to place, manage and control warhead stockpiles on their territory. In this context, the problems of unauthorized access, theft, and cybercrime to seize control of deployed nuclear warheads are raised.

Meanwhile, not all countries are able to obtain permission from the international community to store nuclear stockpiles, which creates a conflict of interest. As one result, such states may invest in building their own weapons, leading to the problem of “illegal” arming of countries wishing to acquire nuclear weapons status. Another important argument against the concept of “the more, the better” is the expansion of the nuclear club, leading to problems of effective communication. At any level of communication, whether interpersonal or international, it is easier to interact with a limited number of partners than to negotiate with all of them. If the nuclear club expands, there is a danger that NPT members will not be able to find common ground with new nuclear powers, which will cause conflicts.

It is noticeable that there is, and will hardly ever be, no consensus on the right strategy for managing the world’s nuclear weapons because it is a highly controversial agenda. Both Waltz and Sagan are right to a certain extent, and since each is interested in achieving international peace, it does not seem right to choose just one concept. Opponents of nuclear weapons theory often argue that national governments spend too much of their budgets to support it. It is true that the money allocated to a country’s nuclear defense could be spent on more humanitarian sectors, be they health, science, or education. However, not investing in the defense of the country might cause a lack of counter-reaction in the hypothetical event of a nuclear attack.

With regard to nuclear weapons, it is also fair to stress that deterring military conflict ultimately proves to be irrational. If, as a result of diplomatic tensions to the limit, the United States decides to launch a nuclear strike against Russia, it would automatically trigger a counter-fire. Obviously, in such a case, neither power would emerge victorious since each side’s expanded arsenal would destroy the enemy and probably all of humanity. This thought again underscores the basis for a theoretical international peace based on recognition of the consequences of nuclear bombardment.

To summarize, it is correct to say that nuclear weapons are humanity’s most ingenious military development, and their creation served as the apogee of the integration of science, technology, and military art. As long as nuclear weapons are recognized as humanity’s most powerful weapons, their possession by a number of countries helps to contain global conflict and thus leads to the conditions of international peace. Naturally, then, international peace is built on the principles of mutual fear, intimidation, and hostility, as this is the foundation of the foreign policy of the nuclear-weapon states. Only if a world built on such foundations can truly be called international peace, then the answer to the question of the relevance of nuclear weapons to it affirmative.

Otherwise, if the philosophical view of international peace is based on categories of mercy, justice, and goodness — in other words, a utopian worldview — then nuclear weapons are antagonistic to achieving such peace. The existence of nuclear weapons is inextricably linked with war, brutality, and violence, so a world with nuclear bombs as its cornerstone would be based on the same principles. For a further, more profound exploration of international peace, therefore, an effective solution is to set out a theoretical framework for international peace. Furthermore, it is interesting to measure whether it is possible to concentrate nuclear weapons in the hands of a few powers in such a way that such an agenda remains just and socially accepted.

Works Cited

Axe, David. “Donald Trump Is A Nuclear President—His Legacy Is More Nukes, Fewer Controls.” Forbes, 2020, Web.

Benner, Katie. “Hunting Leaks, Trump Officials Focused on Democrats in Congress.” NYT, 2021, Web.

CACNP. “Fact Sheet: U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe.” Arms Control Center, 2021, Web.

Colby, Elbridge. “If You Want Peace, Prepare for Nuclear War.” Foreign Aff., vol. 97, 2018, pp. 25-32.

Cronin, Audrey Kurth. “Technology and Strategic Surprise: Adapting to an Era of Open Innovation.” The US Army War College Quarterly: Parameters, vol. 50, no. 3, 2020, pp. 72-84.

Dee, Lizz. “The Fight for Non-Proliferation Begins at Home.” Association for Diplomatic Studies & Training, 2020, Web.

Flom, Peter. “Five Characteristics of the Scientific Method.” Sciencing, 2018, Web.

“100 Incredible Years of Physics – Nuclear Physics.” IOP, 2019, Web.

Karaganov, Sergei A. “On a Third Cold War.” Russia in Global Affairs, vol. 19, no. 3, 2021, pp. 102-115.

Pelopidas, Benoit. “The Birth of Nuclear Eternity.” Futures, pp. 484-500.

Popp, Manfred. “Why Hitler Did Not Have Atomic Bombs.” Journal of Nuclear Engineering, vol. 2, no. 1, 2021, pp. 9-27.

“Putin Unveils New Nuclear Weapons.” YouTube, uploaded by CBC News: The National, 2018, Web.

Sang-Hun, Choe. “North Korea’s Arsenal Has Grown Rapidly. Here’s What’s in It.” NYT, 2021, Web.

Sukin, Lauren. “Credible Nuclear Security Commitments Can Backfire: Explaining Domestic Support for Nuclear Weapons Acquisition in South Korea.” Journal of Conflict Resolution, vol. 64, no. 6, 2020, pp. 1011-1042.

Watts, Sarah. “From Marie Curie to the Demon Core: When Radiation Kills.” Discover, 2018, Web.

Appendix A

Allocation of Roles and Rights According to the NPT (Dee)