Introduction

Turkey is a country with an estimated population of 77.7 million people, and a workforce population of about 20 million people. The country has been undergoing some trade and economic reforms in the last two decades that are a primary reason for its growing commerce and increase in its overall economy. Nevertheless, some external trade factors such as a global crisis event and changes have also challenged the reforms in trade agreements between the country and its major trading partners. This paper explores the importance of the country’s trade to its economic growth as a way of understanding the international trade issues and policies for Turkey. It also breaks down some of its national trade policies and evaluates the exchange rate regime that is currently in place. This is provided in the context of the history of the Turkish Lira’s; the country’s currency, valuation, and changes in the motivation of monetary policies by the government. Lastly, the paper presents the aim of the monetary policy as a tool for controlling the exchange rate and trade. It also explores the potential outcomes for the national currency.

The importance of the country’s international trade in the macroeconomy

Trade plays a significant role in ensuring that there are sufficient capital inflows and appreciation of the local currency to sustain economic growth. The ability to export to other countries in favorable terms will ensure that Turkey can come up with defensive measures for its economy by targeting new markets and ensuring that its exports are competitive in the global market. International trade allows Turkey to tap into big markets beyond its domestic markets, allowing it to increase employment rates for its economy and overall growth. This section looks at contribution to GDP, breakdown of imports and exports, as well as trade challenges.

Contribution to overall GDP

Turkey joined a Customs Union with the European Union (EU) in 1996, which caused a decrease or delay in investments and foreign direct inflows (FDIs) for four years. Political instabilities at the time also negatively affect the country’s economy. Since 2001, there was a changing business environment as the country moved to a free-floating exchange rate policy. Other macro reforms at the time and sustained political stability also caused an increase in investments and FDIs. The country has also been improving its productivity as shown by an overall increase in the volume of exports to its major trading partners in the last decade. Improvement of government policies towards the private sector has played a significant role in most manufacturing companies shifting their focus to the export market. As a result, the economy has also witnessed an increase in its unemployment rate as more manufacturers opt for capital-intensive frameworks that make their products competitive in the global market. They have also been embracing a little value-added structure because much of exported products are also dependent on imports (Ministry of Economy 4-7).

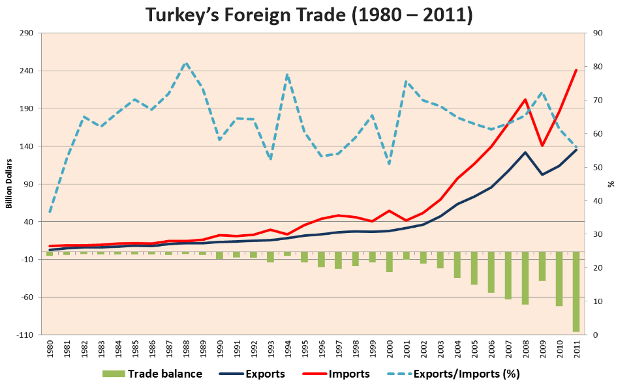

An increase in imports to sustain the export activities by manufacturers coupled with import increases for domestic consumptions have had an adverse effect on exchange rates. The import bill remains the biggest source of depreciation pressure for the Turkish Lira. On the other hand, improved economic fundamentals and proper management of the monetary policy have also caused an appreciation of the Turkish Lira causing disadvantages for exports to the EU where the Euro has been depreciating. The current policy on trade has mainly been market-oriented with few corrective measures by the government, and this hands-free approach threatens to cause a widening trade deficit. In 2011, Turkey had a current account deficit of 10 percent of its GDP.

Dominant exports and imports

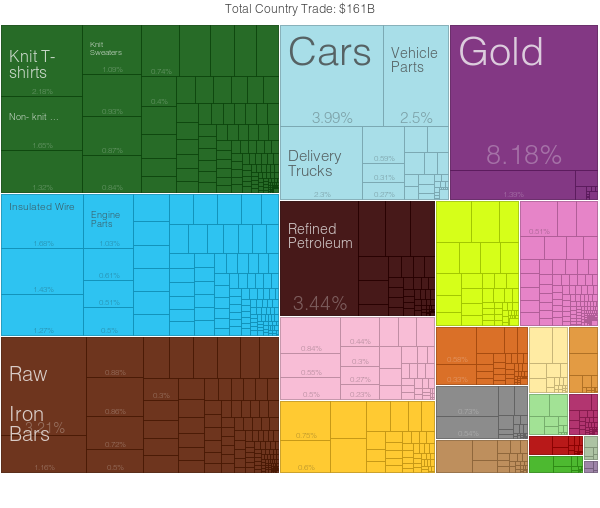

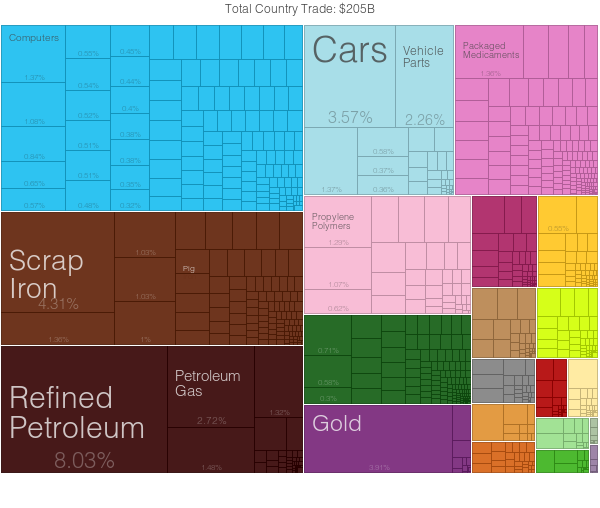

The primary exports from Turkey are gold, cars, refined petroleum, raw iron bars and vehicle parts. Its principal imports are refined petroleum, scrap iron, gold, cars and petroleum gas. It exports to Germany, Iraq, Iran, the United Kingdom and the United Arab Emirates as its major trading partners. At the same time, it imports mainly from Germany, China, Russia, Italy and the United States. The following chart presents a visualization of imports and exports in percentages of their share of trade for Turkey.

Exports have been improving the operation of the European Customs Union agreement with Turkey. Currently, the focus is in high technology sectors where Turkish companies are investing in value addition and development of electrical and electronic products. They are also specializing in machinery and equipment together with various products for the automotive industry. The primary export market remains the EU with the second biggest market being the regions or countries that have free trade agreements with Turkey. An increase in the number of imports in the last two decades has been due to Turkish obligations under the World Trade Organization (WTO) where the country has reduced its customs duties. The country also has fewer protectionism measures and bureaucratic procedures targeted at imports from the Customs Union with the EU.

Current challenges to trade

Turkey ranks at number 41 in the globally Economic Competitive Index of 0.617748 (Observatory for Economic Complexity para. 1). The country has to consider additional options of reducing its current account deficit. Most recently, it has been working on improving its export-oriented manufacturing strategy and working on reforming its incentive system. Particular actions designed to improve exports include the new government approach to international competitiveness through communication on international competitiveness and communication on market access. The country has also increased the number of its trade counselors and emphasized trade in services as a way to ensure that there is a balance of commerce (Ministry of Economy 21).

Lack of sufficient service-based exports and reliance on low value-addition on exports are hurting Turkey’s ability to achieve a balance of trade. The figure below provides a glimpse of the current trade balance reputation in Turkey. It needs urgent intervention, as it is likely to create negative consequences for the exchange rate and the overall economic performance.

Turkey is a neighbor to politically unstable countries like Syria yet its biggest risk to the economic performance and international trade remains within it. Inflationary pressures, political uncertainty and a labor market that is unfit for a purpose serve as the main challenging factors. Turkey is losing a competitive edge because it was unable to contain its inflation. Inflation remains a key component that will allow the country to sustain domestic demand and limit its appetite for imports. Stable prices can help consumers deal with the effects of a weak currency, and manufacturers can be sure about their production costs. Unfortunately, the country expects its inflation to remain high with its 2015 indications being bad for the economy.

As Turkey seeks to boost its exports, it has to continue attracting capital inflows for investment. Unfortunately, an expected increase in US Federal Reserve interest rates will cause increased capital outflows from emerging markets. Being an emerging market, the move will jeopardize Turkey’s options at containing its inflationary pressures and being able to boost growth in trade and overall activity in its economy (Candemir para. 4).

A large population of the working-age population of Turkey is inactive because there is a low rate of female participation in the labor market. Many jobs in the country are in the informal sector, and skills shortages ensure that majority of the adults without tertiary education miss jobs. The current political division of the country also presents political risks as the country moves towards being an authoritarian regime. Also, the proximity to Iraq and Syria on the southern part where much trade comes from is threatening to the overall productivity of the country (Baumphrey para. 3-5).

Other impacts on the economic growth and well-being of the nation

With high inflation, the consumer price index rises. In March 2015, it rose to 7.61 percent from 7.55 percent in the previous month. The country is likely to miss its inflation target of 5 percent in 2015 and this will cause additional pressure on wages as workers seek to increase incomes to cope with the rise in the cost of living (Candemir para. 2).

National trade policies

Turkey appears to favor the building of local competencies of its manufacturing industry. The country has also been pursuing trade agreements that allow it free access to major export markets. However, its partnership with EU countries through the European Customs Union is threatening the country’s ability to sustain a high income per capita. An expected creation of a trans-Atlantic trade agreement between the US and the EU would negatively hit the country’s real income. The country has to come up with ways to ensure that it gains preferential trade treatment with the US before the enforcement of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TIIP). The following subsections examine the country’s international trade agreements and their use of monetary policy to affect exports, imports, and reserves. Despite improvements in the trade policies of the country, its poor business environment continues to affect negatively external participation with many potential firms opting to concentrate on internalization efforts rather than the formation of partnerships or establishment of subsidiaries that would affect positively the export capabilities of Turkey (Stevens para. 5-10).

International trade agreements

Turkey is part of the European Free Trade Association, and it signed the agreement in 1992. In 1996, the country became part of the Customs Union for the EU, which covers trade in various commodities. The country also enjoys bilateral trade agreements with specific countries within the EU that use the agreements as part of their efforts to have a free trade area. The trade agreements give Turkey free or favorable conditional access to markets in return for Turkey also letting business from the partner countries access its market (Turkey para. 1-3). There are about 26 free trade agreements that Turkey has signed so far. Notable countries that have free trade agreements with Turkey are as shown in the table below. In addition to the name of the country, the table also lists the date of signature and the date of enforcement of the particular trade agreement.

Figure 4: Turkey’s FTAs

The country is actively seeking trade agreements with more countries in other emerging markets and major economic regions. Currently, negotiations are in an early stage for bilateral ties with the US, starting with the establishment of a High-Level Committee that is exploring ways to deepen relationships between the two countries (Stevens para. 9).

Use of monetary policy to affect exports, imports, or reserves

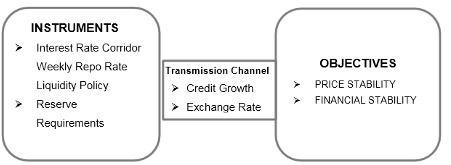

Turkey is a small emerging economy that seeks protection from upheavals in the global economy. The country has been facing volatility in its cross-border capital flows that have caused Turkey to consider financial stability as the overall goal of its monetary policy. The economy contracted in 2009 due to the global economic crisis and then it rapidly expanded because of high domestic demand. There was a surge of capital due to low rates and other economic fundamentals such as government fiscal incentives. The increase in credit growth was accompanied by an appreciation of the country’s currency. However, a stable currency only led to a rise in import demand when the volume and value of exports were still weak, which was an important source of trade imbalance. Starting in 2010, Central Bank has been pursuing a monetary policy that seeks to manage inflation, ensure financial stability and enhance the resilience of the economy. This would be driven by external balance, capital flows and credit expansion. The new policy seeks to avoid a deterioration of current account or volatility in the external financial flows because these two factors create a loop that can lead to a sudden stop of progress. As a strategy for achieving its objective, Central Bank has been working with an interest rate corridor existing in overnight borrowing and lending rates. It also requires liquidity policies and reserves that affect short-term policy rates. The diagram below gives a graphical summary of the Central Bank’s policy instruments and objectives.

Exchange rates

When implementing the new monetary policy, the Central Bank was uncertain of the interest rate corridor and the right amount of reserves to pursue. Much of the existing information about monetary policy in the country was based on previous frameworks, and there was a need for a new transmission mechanism for information that would help validate new elements of credit and exchange rates. As implementation continued, various aspects of the policy became practical, and relevant data emerged to communicate the relationship between credit and exchange rate. Rather than seeking price stability as the only objective, the new policy also considers financial stability. Therefore, the Central Bank does not just follow a policy rate manipulation to affect the inflation rate alone. In addition to the short-term policy rate, the other instruments also come into play.

The Central Bank is embracing a flexible commitment on market rates by adjusting the number of funds that it provides in one-week repo auctions (Kara 8). The strategy gives the Central Bank a chance to manage the monetary stance daily and be able to respond swiftly to risk appetite changes. As a result, the Turkish economy can remain flexible in its response to uncertainties of the global economy, and this has a positive effect on the valuation of its currency. With the new framework, it is possible for the Central Bank to prevent an excessive depreciation of the country’s currency by reducing liquidity in the market and letting short-term rates rise. The rates cause a reversal in capital outflows as they make the local economy more attractive to international capital, which would be against the global circumstance that led to the move by the Central Bank. Therefore, an effect of the new monetary policy framework has been to manage the attractiveness of Turkish markets by allowing the smooth flow of capital in and out.

Besides, the Central Banks gives local banks an option to use a ratio of Turkish Lira-required reserves in foreign exchange or gold. The arrangement allows banks in addition to the Central Bank to be able to deal with fluctuations in capital flows that affect the exchange rate and the country’s financial markets. When there is an increase in capital inflows, banks can keep more of their required reserves in foreign exchange. In return, the exchange rate will not have to appreciate as fast as it would without the bank reserves and this works as a way to reduce the sensitivity of the economy and the exchange rate to capital flows (Kara 13).

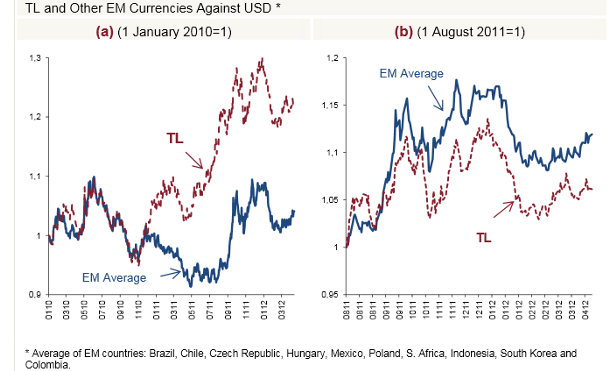

Because of implementing the 2010 policy framework, the country has been able to move its currency towards the desired economic fundamentals, with a slow of credit to reasonable levels as indicated in the figure below. The value of the Turkish Lira has matched the values of peer currencies, but it faced limited depreciation against the US Dollar despite the fact that global risk appetite had deteriorated after August 2011. Moreover, the policy has also helped the country deal with the abrupt swing of domestic financial markets caused by the Euro area debt crisis. In fact, the Turkish Lira had a correction when the Eurozone sovereign debt problems were yet to show a risk of a sudden stop in capital flows. Otherwise, Turkey would succumb to the shock. The soft landing of its currency and the economy was a manifestation of the capabilities of the 2010 monetary policy framework.

Free-floating or controlled?

The Turkish Lira, which is the official currency of Turkey, has a value that depends on market equilibrium conditions for its supply and demand. The currency relies on the amount of the foreign currency reserves held by the Central Bank of Turkey as well as other market factors such as external developments, political climate and overall demand for imports and volume of exports from Turkey. Also, the Central Bank plays an important role in seeking to control the value of the currency. It has recently been taking various monetary interventions to ensure that the currency does not depreciate.

Turkish companies with foreign debts have to pay the debts in foreign currency and in doing so; they increase the demand for the foreign currency against the demand for the Lira. When there are too many fluctuations that are also severe, the balance sheets of the respective companies suffer, and in extension, the Turkish economy is affected. This is the main reason behind control tendencies exhibited by government entities as explained in the next section on the use of monetary policy by the Central Bank of Turkey.

The move to a floating exchange regime began in 2001, and it led to an economic crisis in February of the same year. However, a new program created with help from the International Monetary Fund stabilized the economy. The country then began targeting inflation formally in 2006 and focused on that and foreign exchange liquidity up to 2010, when a new comprehensive monetary policy was adopted. The previous section of this paper discusses this policy and its effect on the exchange rate.

Use of monetary policy for control

The central bank has had a monetary policy specifically aiming for the valuation of the Turkish Lira. In 2014, Turkey hiked its base rate by 5.5 percentage points. As a result, the currency was able to rebound against the dollar and sustain an upward value trend throughout the local election that was held at the end of March of the same year (Cetingulec para. 5-7). Besides efforts by the Central Bank, the Government of Turkey, through its economic policies has also been controlling the valuation of the currency with an aim of making it stable and strong against other major global currencies like the US Dollar and the Euro. The Central Bank has been actively increasing its foreign currency reserves since 2014 and hopes to balance the accelerated inflow of capital. The Bank has also opted to refrain from selling dollars at certain times so that it does not upset the supply of dollars in the currency market and negatively affects the valuation of the Turkish Lira. In defending its action, the Central Bank of Turkey has repeatedly denied claims of making the country’s currency artificially strong. Instead, it has said that its monetary policy actions aim to prevent unnecessary sliding of the currency based on temporary market conditions.

Future of the national currency

The national currency has a flaky future because much of the country’s exports, 45 percent, are payable in Euros. On the other hand, the state pays 65 percent of its imported goods using dollars, and it only pays with the Euro on 30 percent of imports (Demirdoven para. 1-2). Thus, the country is vulnerable to changes in both the Euro and the US Dollar valuations. A depreciating Euro against the dollar will cause Turkey to suffer whereas an appreciation of the US Dollar will also be bad because of the country’s import bill. Nevertheless, inroads made into the common European market for exports mean that its exposure to the Euro’s depreciation is low.

Overall, the demand for the Lira depends on the trading activity of Turkey and the European Union as well as the US. Besides that, the respective monetary policies by the two trading partners will affect their currency valuations and affect the demand of the Lira, hence its valuation. The European Union has been facing poor economic activity, and this will continue contributing to the depreciation of the Euro and subsequent strengthening of the Lira against it. However, the US Dollar will likely gain more due to present negotiations for a transatlantic trade agreement. Besides, the increased dominance of the US as an important oil producer and the overall lowering of petroleum prices across the world have also caused the depreciation of the Euro. Thus, with the Euro dominating Turkey’s exports, its fall will negatively affect the Lira (Demirdoven para. 6-7).

Based on its performance in recent months, the Lira should continue depreciating; however, its rate of depreciation will be stable due to monetary activities by the Central Bank. Government efforts to influence trade will also assist in arresting the depreciation and causing stability in Lira. Nevertheless, much of the currency’s value is dependent on international trade and monetary policy dynamics that offer Turkey limited control. In the medium-term, Turkey may have problems with its mechanisms for arresting the decline of the Lira because of capital outflows to the US. Although the current monetary policy framework has been effective at sustaining a smooth flow of capital, it is unable to reverse or stop flows efficiently. Therefore, the gradual depreciation should continue unless the interest rate circumstances in the US change. Another currency problem will arise from importation because the rate of exports increase is significantly less than that of imports. Imports are unlikely to subside given that additional free trade agreements and bilateral negotiations will expose the Turkish markets.

Works Cited

Baumphrey, Sarah. “Turkey’s Five Big Challenges.” Today’s Zaman, 2014. Web.

Candemir, Yeliz. “Turkey’s March Inflation Rate Rises to Three-Month High.”. The Wall Street Journal, 2015. Web.

Cetingulec, Mehmet. “Turkey’s Currency Prepares For A Fall.” Al-Monitor, 2014. Web.

Demirdoven, Furkan. “Uncertainty Over Currency Seems To Be Affecting Turkish Trade-In 2015.” Today’s Zaman, Web.

Kara, A Hakan. Monetary policy in Turkey after the Global Crisis. Ankara: Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey, 2012. Web.

Ministry of Economy. “Exchange Rates – Trade: Turkey Case.” World Trade Organization, 2012. Web.

Observatory for Economic Complexity. “Learn More about Trade in Turkey.” 2015. Web.

Stevens, Philip. “Time to Talk Turkey on Trade.” The Hill, 2015. Web.

“Turkey.” 2015. EFTA. Web.