Introduction

The marine areas of the East China Sea, where the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands are located, are abundant invaluable environmental resources, including oil and natural gas. Both Beijing and Tokyo claim their rights to these territories and have long been unable to agree on a maritime boundary. The presence of both states’ military aircraft and naval forces in the region raises particular concerns about potentially armed hostilities, especially given the international agreement that may also involve U.S. armed participation. In this policy paper, the UN provides contextual data on the dispute in the East China Sea, analyzes it and similar cases, and proposes possible policy options and recommendations.

Context of the Dispute in the East China Sea

The Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands have been under Tokyo’s administrative control since they were returned to Japan in the early 1970s after a certain period of being under U.S. jurisdiction. In 1968, based on studies conducted under the auspices of the UN, it was concluded that there might be oil and gas reserves in the East China Sea (Klare, 2014). China subsequently asserted its claims to these territories, pointing to its historical rights and referring to them as originally Chinese.

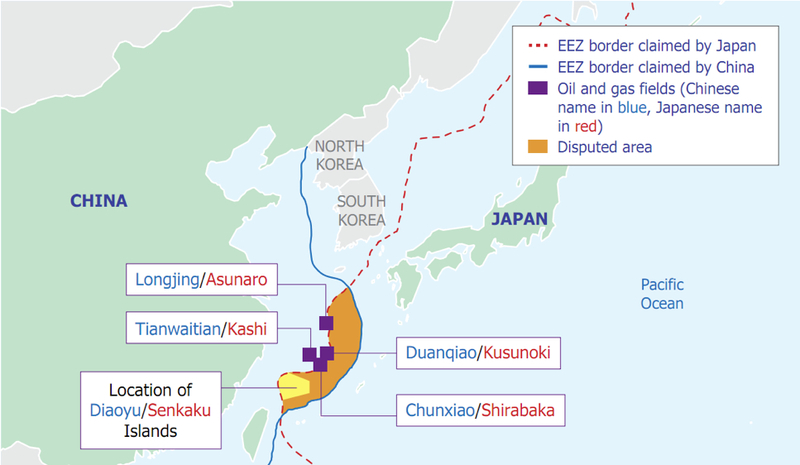

The disputed area of the East China Sea was originally Japan’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ). However, Beijing also declared this territory as its EEZ and ADIZ in November 2013 as illustrated in Figure 1 (Klare, 2014). According to Liff and Erickson (2015), both states have increased their military presence in the region, both in water and air, and China is conducting an unprecedented number of military maneuvers. Nevertheless, the States agreed to resolve all issues exclusively through negotiations, without resorting to the use of force.

This dispute is aggravated by the possible involvement of U.S. military forces in the event of armed conflict. Between 2007 and 2012, Tokyo and Beijing held several negotiations on the interaction of navies in the disputed region. Liff and Erickson (2015) state that the governments discussed the “implementation of a hotline between defense authorities to avoid unintended clashes in the air and at sea” (para. 5).

These diplomatic arrangements were favorable to all parties of the dispute, including the U.S., which could enter into a military confrontation on the Tokyo side according to the Mutual Defense Treaty of 1954 with Japan (Klare, 2014). Nevertheless, the period after 2012 has been marked by a continued escalation of the conflict.

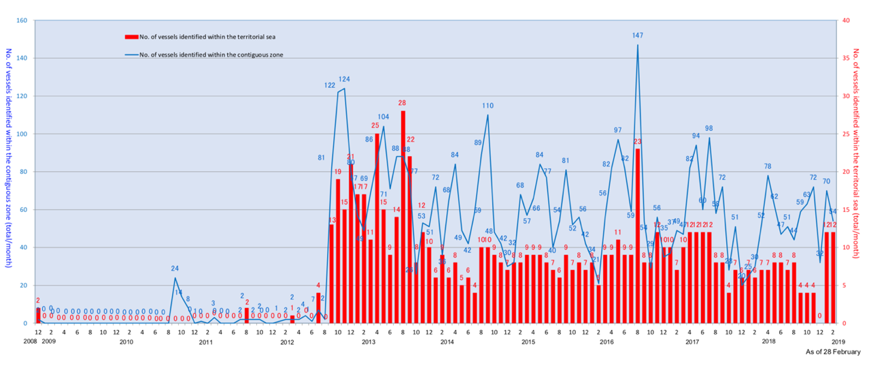

The Japanese government announced the nationalization of three of the five Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, which led to mass anti-Japanese demonstrations in China. Furthermore, in retaliation, Beijing dispatched more military vessels and aircraft to the Japanese territorial waters border, resulting in several dangerous encounters in the water and air. Since 2012, there has been a critical increase in the number of Chinese naval vehicles crossing the territorial waters and contiguous zone of Japan as illustrated in Figure 2. The UN believes its role is to facilitate a peaceful resolution of the dispute and to help the parties to agree on the joint exploitation of the reservoir.

Analysis of Evidence and Best Practices

The UN takes into account that the armed clash is the least desirable scenario for all parties to a dispute. Consideration should be given to its factual circumstances, similar cases in international legal practice, and the applicable rules of international law. Researchers note that both sides understand that the war will be a non-win undertaking, but at the same time, neither Beijing nor Tokyo agree to recognize the sovereignty of the opposing state in disputed territories (Carlson, 2013). To this end, it would be advisable to analyze each aspect of the dispute to apply the various negotiating and regulatory instruments to them, where possible.

The most urgent issue that needs to be resolved is the military presence of both nations in the region. This dispute generally concerns the delimitation of the territorial boundaries of the two States into disputed maritime zones and archipelagic territories. States. Both China and Japan have signed and ratified the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UN CLS). According to it, “parties shall settle any dispute between them concerning the interpretation or application of” the “Convention by peaceful means” (UN CLS, 1982, p. 129). Thus, the demilitarization of the region is a principal objective for both parties and the UN.

Other priorities are, on the one hand, determining the party to which the right to natural resources belongs and, on the other hand, setting the maritime boundary between the two states. It should be noted that, as a rule, these disputes are settled with the participation of international arbitration courts or special judicial bodies established by international agreements. For instance, a similar dispute was the subject of a Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) proceeding in a case between the Philippines and China concerning an archipelago in the south-western South China Sea in 2013 (Philippines v. China, 2015).

Although China neither accepted the jurisdiction of the PCA nor participated in the proceedings, the PCA affirmed its jurisdiction and ruled in favor of the Philippines. For the above reasons, this decision did not have any actual effect, and therefore the consent of both parties to a jurisdictional settlement of the dispute is required in this case.

Policy Options and Recommendations

The UN invites all parties to resolve the issue of the region’s demilitarization during the Geneva Conference by defining clear boundaries for the permitted stay of military vessels and aircraft of both states. If the parties do not define these borders in the course of the meeting, the UN proposes the introduction of a Security Council peacekeeping forces in the East China Sea. Their main objective will be to prevent possible military clashes or fatal accidents. In addition, China and Japan should agree on a settlement of non-crossing ADIZ at the earliest opportunity.

The dispute arose after the discovery of oil and natural gas reserves in the East China Sea. It should be assumed that the main interest of the parties is precisely to gain access to these resources. According to Wright (2012), “China objected to the ‘multilateralization’ of maritime disputes” and continues to hold that position (para. 6). Given this circumstance, Beijing and Tokyo should make their best efforts to rule on the joint exploitation of the reservoir or agree to submit the dispute to an international court.

It should be noted that the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea functions by the UN CLS. According to it, “the jurisdiction of the Tribunal comprises all disputes and all applications submitted to it by this Convention” (UN CLS, 1982, p. 183). The same considerations apply to the territorial boundaries between China and Japan. The UN proposes to agree on an additional conference if the disagreements are not resolved during the Geneva meeting.

Conclusion

The military presence of air and naval forces of Beijing and Tokyo in the East China Sea, as well as the overlapping Air Defense Identification Zones of both states, has already led to dangerous military encounters. It is threatening armed clashes and the involvement of US military troops. The UN considers three principal areas of negotiation during the Geneva meeting. These include the demilitarization of the region and the introduction of the Security Council peacekeeping forces, the decision to develop natural resources jointly, and the determination of the permanent water boundaries between Japan and China.

References

Carlson, A. (2013). China keeps the peace at sea. Foreign Affairs. Web.

Klare, M. T. (2014). The end of ambiguity in the East China Sea. Foreign Affairs. Web.

Lee, I., & Ming, F. (2012). Deconstructing Japan’s claim of sovereignty over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands. The Asia-Pacific Journal, 10(53). Web.

Liff, A. P., & Erickson, A. S. (2015). Crowding the waters. Foreign Affairs. Web.

Lu, C. (2020). China’s Evolving Policy toward Japan in the East China Sea: What’s the Next Move? Foreign Policy Journal. Web.

The Republic of the Philippines v. The People’s Republic of China, PCA Case Nº 2013-19 (2015).

UN General Assembly. (1982). Convention on the Law of the Sea, December 10, 1982. New York, NY: UN General Assembly.

Wright, T. (2012). Outlaw of the sea. Foreign Affairs. Web.