Introduction

The United States (U.S.) tragedy on the morning of Tuesday, September 11, 2001, marked a new chapter in the nation’s opposition against international terrorism and was the major event that changed the military’s approach to warfare. President George W. Bush defined the 9/11 attacks on America as “a new war, with the only difference between previous wars being magnitude, and marked the attack as a turning point in history” (Kakihara, 2003, p. 2).” Since the 9/11 attack, the military has had to think differently about warfare (Jenkins & Godges, 2011). The attack initiated a shift in the U.S. military’s strategy requiring the deployment of forces and the active engagements with foreign nations’ civilian populous, reflecting apurely transitional approach. Military veterans who have served after the 9/11 attack, referred to as post-9/11 veterans, have been exposed to combat deployments more frequently than the previous military generation, therefore having a distinguished mindset (Parker et al., 2019).

A military mindset generally refers to how you process information, how you carry out tasks, and how one interacts as part of a team – qualities highly praised in military organizations and the civilian workforce (Pollak & Arsbanapalli, 2019). Veterans are highly desirable candidates for civilian jobs because of the skills they learned during their time in uniform, not despite them (Citroën, 2017); thus, it is commonly acknowledged companies can benefit from the competencies veterans possess. Unfortunately, despite the growing number of post-9/11 veterans in the country, this group’s competencies and competitive advantages in a business setting are significantly under-researched (Aronson et al., 2019). The study attempts to narrow the research gap and examine the benefits of post-9/11 veteran’s competencies in a business sphere.

Through the research, businesses may incorporate post 9/11 veteran’s competencies so that they can be able to take advantage of the skills in encouraging other employees to improve organization performance. Further, research on the competencies acquired in their military years serves to align other employees towards pursuing common organization goals through streamlined decision-making and problem solving. The possibilities and potential benefits of employing or retaining post-9/11 military veterans in business organizations could improve leadership practices, talent management, and as a consequence, the organizational culture. The unique skills for the civilian workforce include leadership, discipline, resiliency, and teamwork. Nevertheless, employers also remark the peripheral skill set of the military veterans, including maturity, adaptability, courage, organizational commitment, and trustworthiness. The mission-focused mindset of veterans distinguishes the skills of this group from the civilians it will be essential to thoroughly analyze each of the core competencies shared by generational military veterans.

Background

Previous research has found that military veterans and civilians associate the military mindset with such qualities as teamwork, leadership, resilience, and discipline (Parker et al., 2019). These recognized competencies significantly improve employees’ productivity and positively affect the organizational culture in the business setting (Stackhouse, 2020). Therefore, it is essential to provide a thorough description of these qualities to examine their potential effect on the business groups in an internal workspace and evaluate the efficiency of an organizational business strategy for specifically post-9/11 veterans.

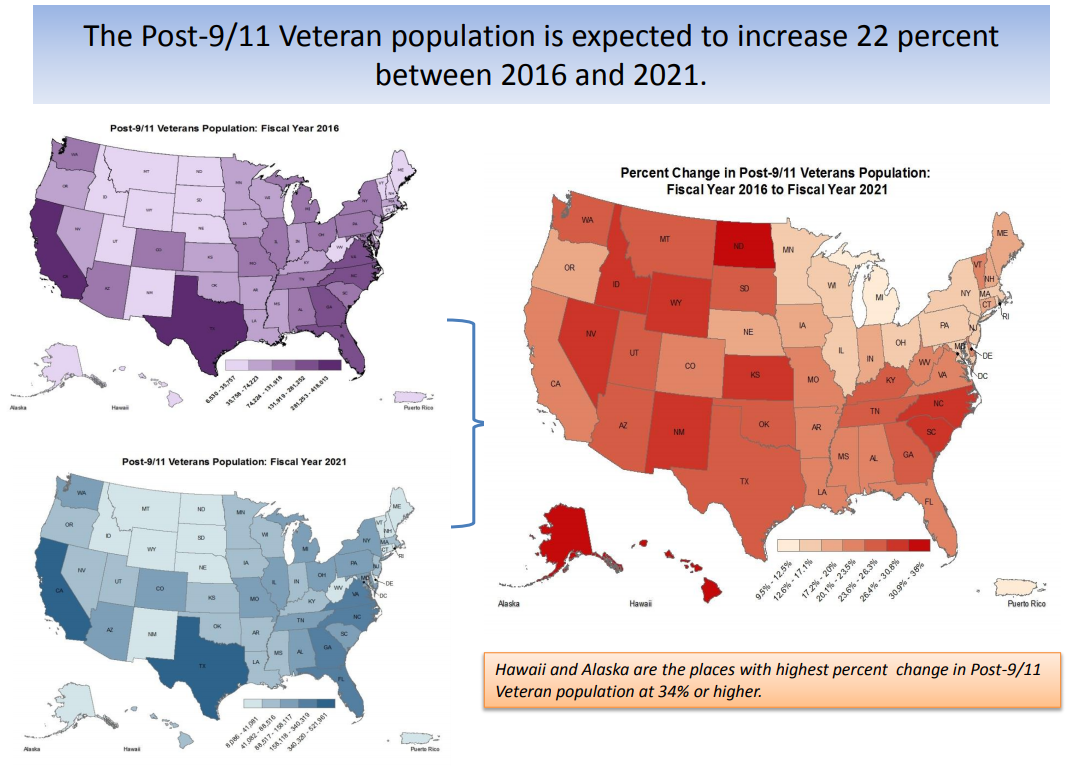

At present, the comprehensive generational qualities of the military mindset are relatively well-studied; yet examinations of the competencies of post-9/11 veterans specifically are heavily under-researched. The research gap includes the competencies of the post-9/11 military mindset that are transferable in a business setting, the competitive advantages of hiring post-9/11 military veterans, and their benefits to the organizational business culture. Currently, there are more than three million post-9/11 veterans, and the number is expected to rise in the next five years (Aronson et al., 2019). The statistics imply that post-9/11 veterans will constitute a more significant portion of the civilian workforce in the upcoming years; therefore, it is beneficial to businesses and veterans to identify the advantages and cultural effects in a business setting.

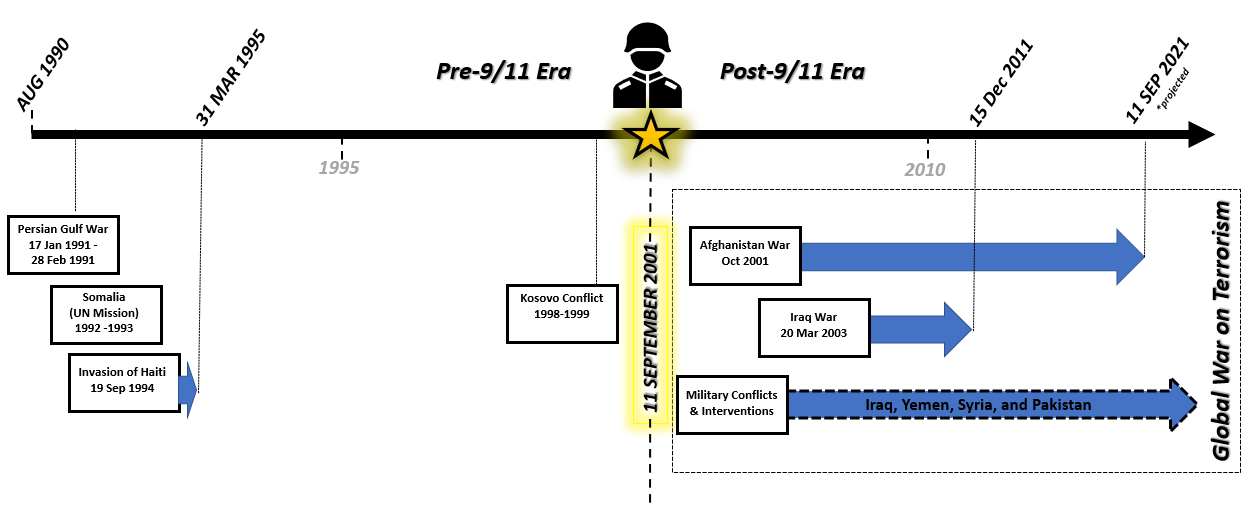

The core qualities of a military mindset include teamwork, leadership, resilience, and discipline, and all these competencies might significantly affect the organizational structure and culture of a company. Although several scientific studies have been conducted to analyze these competencies comprehensively, the academic works generally address the qualities of a military perspective without the context; as a result, the unique characteristics of the military mindset of the post-9/11 veterans are heavily under-researched. As noted earlier, post-9/11 veterans have undergone a more intense exposure to combat, a higher percentage of deployments, and more demanding military experiences than previous generations (Parker et al., 2019). Thus, an assumption is concluded that the differences in training and prolonged exposure to deployments or combat reflect acquired skill sets and a philosophy gained from those experiences; thus, it is essential to thoroughly investigate the peculiarities of the post-9/11 veterans’ military mindset, specifically. Figure 1 is an illustration of the comparison of military engagements and conflicts of the pre-9/11 (August 1990 – September 2001) and post-9/11 (September 2001-Present) military generational eras.

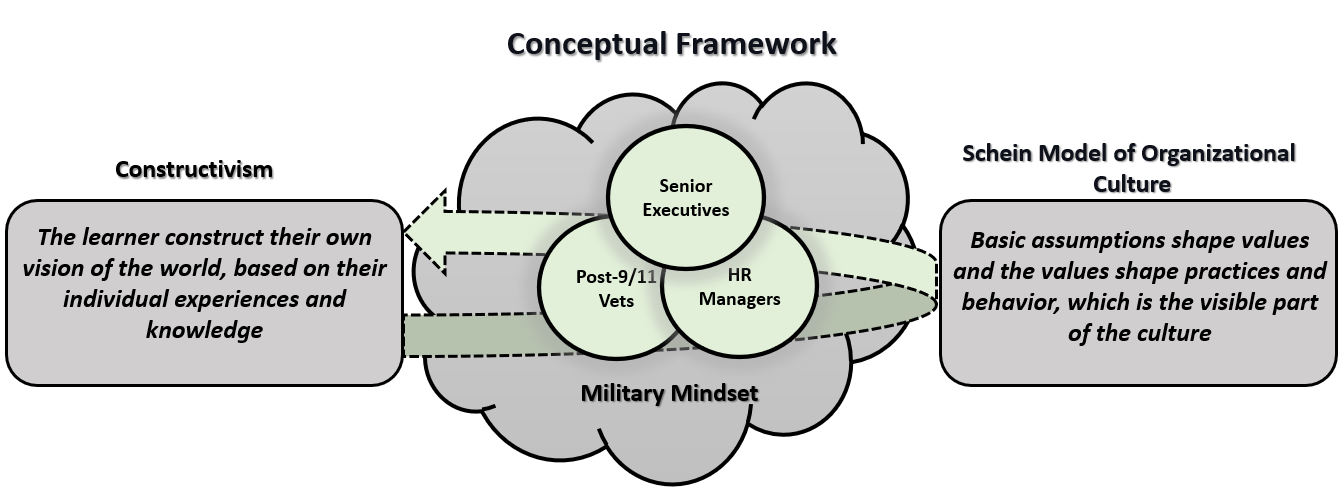

This study intends to utilize two primary conceptual frameworks – Constructivism and Schein Model of Organizational Culture – to evaluate the said qualities and assess their impact on the organizational culture. Constructivism is an “approach to learning that holds that people actively construct or make their own knowledge and that reality is determined by the learner’s experiences (Elliott et al., 2000, p. 256).” Constructivism’s central idea is that human learning is constructed; learners build new knowledge upon the foundation of previous education. This prior knowledge influences an individual’s new or modified knowledge from new learning experiences (Phillips, 1995). The second conceptual framework is the Schein Model of Organizational Culture, which evaluates the mindset effect on the organizational culture (Schein, 2016). Ultimately, the chosen frameworks provide beneficial insights into the competencies of post-9/11 veterans’ perspectives and narrow down the research gap. The subsequent chapter presents a thorough description and details of the two models cited above.

This study intends to examine the said phenomenon of the competencies of post-9/11 veterans’ mindset and the applied organizational strategies in the setting of one company. The focus on a single business provides the ability to focus the scope of the work and conduct in-depth qualitative research to learn perspectives from employees and executives in an individual organization. Previously conducted secondary research and the theory of the study suggest that the qualities and competencies of post-9/11 veterans differ significantly from the previous military generations. Therefore, it is essential to acquire empirical data from post-9/11 veterans, Human Resource (HR) specialists, and senior executives in an operating business. As a result, the selected company for the project is Yorktown Systems Group (YSG). Chapter 2 provides a thorough description of the organizational structure and composition.

The growing number of post-9/11 veterans in the U.S. is a significant social and practical concern due to the lack of specific research on the topic. The current study’s findings could prove to be highly beneficial in providing extensive insights for post-9/11 veterans and businesses. The results of this study cannot be generalized to all enterprises or the entire population of post-9/11 veterans; nevertheless, the study aims to contribute to the further advancement of academic and practical knowledge concerning the topic.

The benefit of the research, to post 9/11 veterans, was that veterans can use the skills they acquired serving in their military years to be used in civilian organizations when recruited to work in such places. It means veterans have an opportunity to apply their skills in civilian organizations and help them take their mind off from traumas that associates with service. Further, the research will help them in understanding how they can transition from military to civilian life and more significantly, from military to key members in business organizations. To Yorktown Systems Group, the findings help it in evaluating the significance the skills acquired in military can change how it will improve its performance. Further, it will help improve on the significant and diverse human capital that can be incorporated to best align its processes and policies in achieving its functions.

Statement of the Problem

The study seeks to examine YSG’s cultural-organizational challenges that are attributed to inconsistencies, poor communication, and ambiguity that hinders it from achieving organizational success. When organizations suffer from challenges associated with organizational culture, their employees encounter an unpleasant ad hostile environment that impacts performance. Potentially, due to such encounters, workers become less loyal and in this state, episodes of bullying, harassment, and high turnover are often reported. Inclusion of post-9/11 veteran’s generational military competencies combined with the acquired KSAs learned during their post-9/11 military service may benefit YSG in its business organization and in turn its organization culture. The inclusion will help the organization to streamline its organization culture. Military veterans acquired transferable organizational skills that arise from the knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSA) derived from their experiences of post-9/11. Similar traits and skills are essential in how military veterans transition after the 9/11 attack and those veterans’ adaptation to a civil-military atmosphere offered unique and innate experiences that are advantageous in a business environment. Therefore, by incorporating veterans in YSG, the organization will gain organization skills that will help its organization culture and improve performance.

The study seeks to examine if YSG’s cultural and organizational success is directly related to the competencies of its post-9/11 military veterans’ workforce. YSG is a professional services company providing customized solutions and management capabilities to federal and civil organizations and has accumulated sufficient industry growth since its inception in 2008. A significant number of the organization’s employees are veterans; however, it is unknown if its development and expanding business scope are directly related to its military veterans’ workforce.

As mentioned briefly before, the overall number of post-9/11 veterans is gradually increasing and may exceed four million veterans by the year 2024 (Aronson et al., 2019). Therefore, the statistics imply that a growing number of post-9/11 veterans are transitioning to the civilian workforce (McCormick et al., 2019). On the organizational level, businesses have a vague understanding of the potential benefits that post-9/11 veterans can contribute due to the lack of research in this field (Stackhouse, 2020). Lastly, further study analysis is beneficial to the societal level by providing research to promote programs and services concerning the employment of post-9/11 veterans (Morgan et al., 2020)

While employing pos-9/11 veterans might be beneficial to organizations, the laxity to incorporate their competencies is a struggle by several organizations, and not specific to YSG. Incorporating veteran military competencies is essential since it will help determine the benefits the organization stands to gain by incorporating veterans competencies in its culture, future, and bottom line. For organizations, military-to-organization skill set values are transitioned when the acquired military methodologies and skills are translated in the context of the company. Through this translation, firms are better positioned to incorporate focused execution, excellence, and best-in-class performance. Nonetheless, even with the understanding, a majority of businesses in the country do not realize this advantage. Most civilian leaders believe the competencies worked best in combat yet fail from utilizing the same mindset used in combat in handling their business operations, which can be easily handled through the competencies.

A literature gap exists that identifies business advantages from the experiences of post-9/11 veterans that build upon the competencies of previous military generations. After examining the theoretical background of the military mindset of post-9/11 veterans, it was possible to identify the research gap and state the research problem. The research gap represents a lack of sufficient literature concerning specific business competencies of post-9/11 veterans. Many studies present comprehensive generational military data regarding various qualities of a military mindset, such as teamwork, leadership, resilience, and discipline, and provided sufficient evidence of the utmost importance of these competencies in the business setting (Pollak & Arsbanapalli, 2019). Consequently, the statistics demonstrate the significant differences between the military experience and the combat exposure of post-9/11 veterans and previous military generations (Parker et al., 2019). In theory, the contrast between pre-9/11 and post-9/11 veterans should establish specific differences in the mindsets of veterans and be reflective in the transition to the civilian workforce. The lack of research and significance of the study’s transparent application in individual, organizational, and societal levels indicates the need for further examination.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this qualitative case study is to explore the leveraging of the post-9/11 military mindset competencies to examine the associated competitive business advantages and the post-9/11 veteran’s effect in organizational culture. The study intends to explore the competencies of post-9/11 veterans in a business setting utilizing qualitative research methods to ensure in-depth research of the analyzed phenomenon. According to the problem statement, a qualitative approach is chosen since it is essential to provide non-numerical data, including narratives, perspectives, and attitudes, of post-9/11 veterans, HR managers/specialists, and senior executives concerning the topic. Although quantitative research could provide supplementary information in similar research, it fails to address the study’s problem statement—therefore should not be used as an effective method of data collection (Basias & Pollalis, 2018). Consequently, this study is a qualitative case study with a sole focus on one organizational entity.

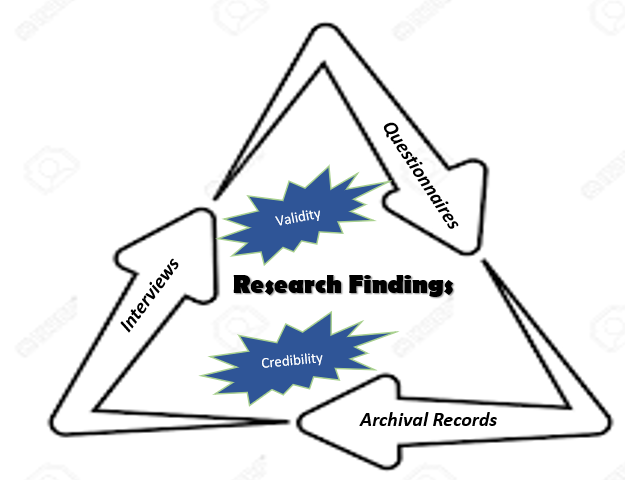

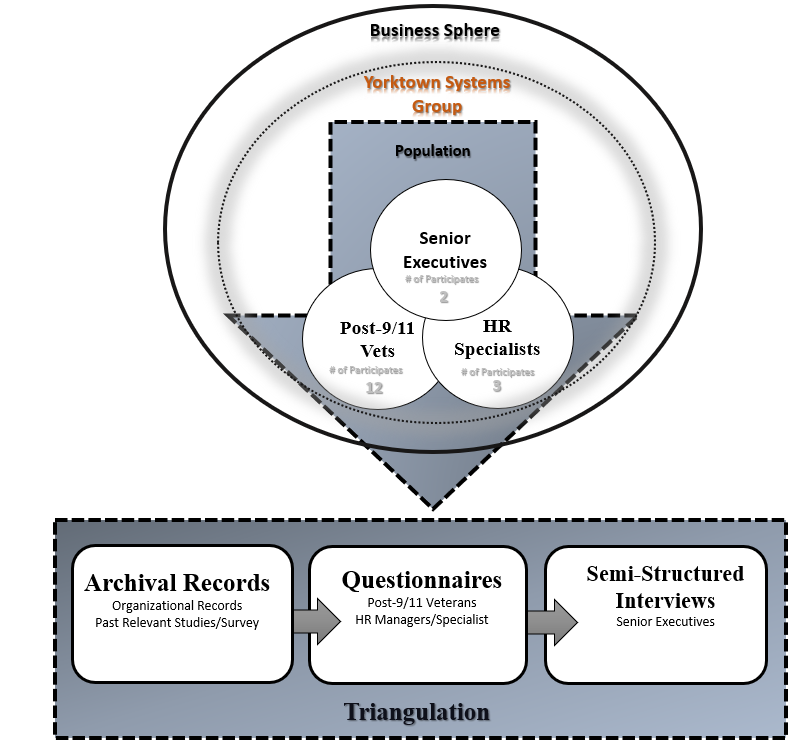

The participants are employees of YSG with an emphasis on post-9/11 veterans of various occupations, HR managers/specialists, and senior executives. Organizational data is derived from archival records, and the three targeted groups will participate in questionnaires or semi-structured interviews. The data collection questions focus on the problem statement and the purpose of the study; therefore, they differ slightly for each targeted group. The three sources of data collection ensure the reliability and validity of the collected data, and different questions guarantee a more comprehensive overview of the topic. The convergence of information from other sources is a qualitative research strategy to test validity through triangulation. However, the purpose of triangulation is not necessarily to cross-validate data but rather to capture different dimensions of the same phenomenon. Figure 2 below illustrates the proposed data collection instruments to test the study’s validity.

In the current health environment, it is impossible to conduct in-person interviews at YSG’s geographically dispersed sites due to the risks of COVID-19 and the consequential restrictions. Therefore, the semi-structured interviews and questionnaires will be completed and recorded via online applications. The other source of data collection, archival records, will perform an artifact analysis and document retrieval of relevant information relevant to this study (e.g., company policy letters, internal memos, and previous data/studies pertinent to the study). Ultimately, the chosen research method and the purpose statement are appropriate to address the research problem. Chapter 3 provides a comprehensive overview of the project methodology.

Conceptual Framework

The theoretical background and conceptual framework comprise the foundation for the study to ensure a logical structure and organization for the research. As mentioned before, the study utilizes two primary conceptual models – Constructivism and the Schein Model of Organizational Culture. A proposed theory of the research is that the competencies of the mindset of post-9/11 veterans differ significantly from the perspectives of previous military generations due to more intense exposure to combat (Parker et al., 2019). The constructivism theory supports this assumption and states that every skill or competency is learned and affected significantly by practical experience and social context (Johnson, 2019). Many researchers have provided sufficient evidence concerning the learning-based nature of such skills as leadership and discipline, which are the core features of the military mindset (Kirchner & Akdere, 2017). Therefore, applying the constructivism approach to the military mindset of post-9/11 veterans provides insights into the acquisition of acquired military knowledge and skills and their relevance in the business setting.

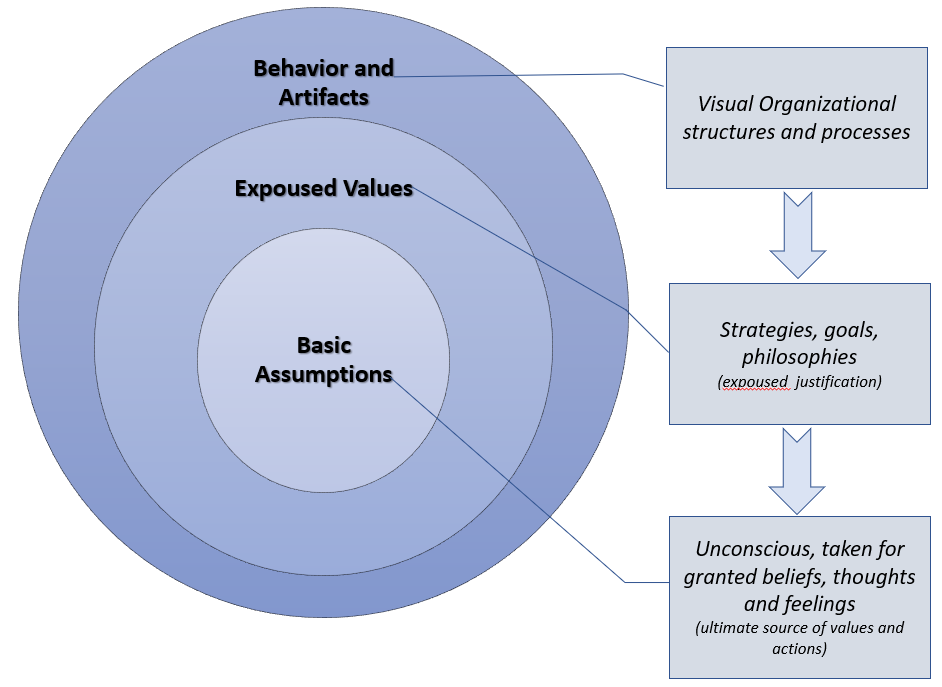

The second conceptual framework to be implemented in the study is the Schein Model of Organizational Culture. Unlike constructivism, the Schein Model of Organizational Culture is not used to determine the nature of the acquired competencies but to examine the application of the said skills in organizational culture (Schein, 2016). According to the theory, the employees’ competencies and previous experiences directly affect the company and the relationships between the workers (Schein, 2016). The primary elements of organizational culture include behavior, espoused values, and basic assumptions (Schein, 2016). In the scope of the current study, the model implies that the unique experience and multiple deployments of post-9/11 veterans could benefit the organizational culture by stimulating discipline and a culture of respect. Consequently, the exposure to socially praised qualities, such as leadership and teamwork, might enhance the overall atmosphere in the company and reduce the prominence of hidden assumptions and other forms of prejudice (Schein, 2016). Ultimately, the Schein Model of Organizational Culture is an appropriate theoretical model to determine the influence of the post-9/11 veteran’s mindset on the organizational culture of a business.

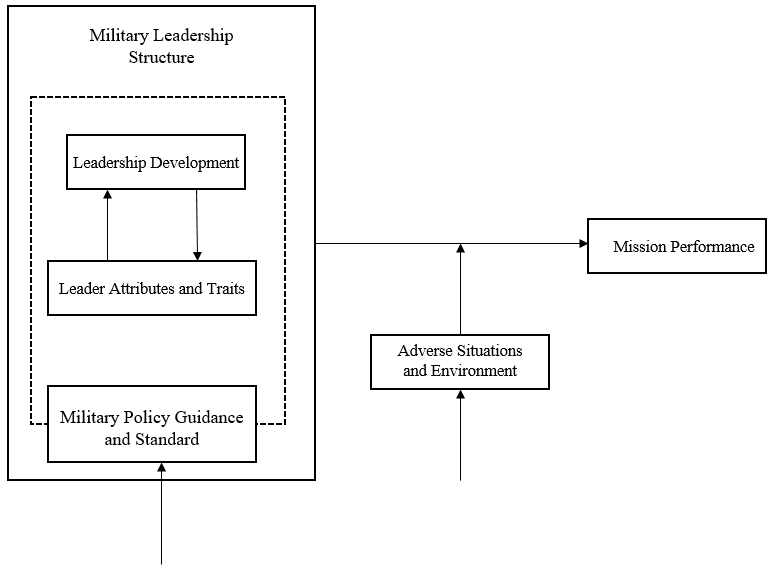

As a result, applying the two presented conceptual frameworks in data collection and analysis might provide beneficial insights concerning the unique nature of the military mindset of post-9/11 veterans and its relevance in the business setting. Both models are widely accepted in the academic community and used prior for similar research objectives (Kirchner & Akdere, 2017; Schein, 2016). Figure 3 illustrates the conceptual frameworks of the proposed study.

Ultimately, Constructivism and the Schein Model of Organizational Culture appear appropriate theoretical models for this study. The proceeding chapter presents specific details about the study’s conceptual frameworks.

Research Questions

The listed open-ended research questions align with the purpose statement and the conceptual framework:

- RQ1. What are the competencies of the post-9/11 military mindset that are transferable to YSG’s business setting?

- RQ2.What competitive advantages or benefits dodoes YSG possess through the hiring of post 9/11 era veterans?

- RQ3. How can YSG incorporate these competencies and advantages to facilitate organizational success?

The first research question concerns the unique nature of the competencies of the military mindset of post-9/11 veterans, and the others address the impact of these qualities in the organizational structure. The guidelines for questionnaires and semi-structured interviews are based on the identified research questions and differ slightly, depending on the target group. Appendix C and D provide questions used to enlist responses from participants for each targeted group.

Method and Design Overview

The project utilizes the qualitative research method and case study research design. The qualitative approach ensures the analysis of the subject and its alignment with the purpose statement and research questions. Contrary to quantitative methods, qualitative case studies emphasize non-numerical data, such as narratives, perspectives, beliefs, and attitudes (Basias & Pollalis, 2018). The proposed primary data collection methods implemented in the study are archival records, questionnaires, and semi-structured interviews. The simultaneous use of three various sources of information are called triangulation, which contributes to the validity and reliability of the gathered data (Alam, 2020). The primary advantages of the qualitative research method are in-depth analysis, the proximity of the researcher to the target group, and the adaptability of the approach to the goals and research questions (Queirós,et al., 2017). As a result, qualitative research was deemed appropriate for exploratory case studies emphasizing specific phenomena.

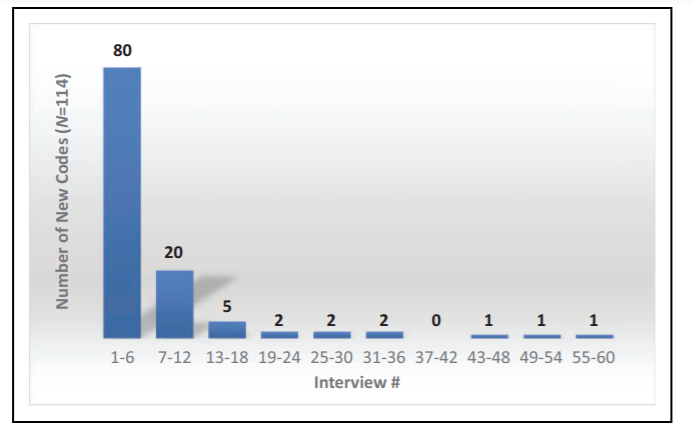

The sampling for the study is determined via criterion strategy and the sample size is seventeen participants, which is an appropriate number for qualitative studies (Moser & Korstjens, 2018). Consequently, the collected data will be processed and analyzed via the manual examination and the web-based software Dedoose. Through Dedoose, the gathered data will be imported by design via a spreadsheet that has automated descriptor fields. The software will then create descriptors and codes, and convert any information as they correspond to tagged excerpts in documents for every case. Lastly, Dedoose will automatically link the document to the descriptor that is deemed appropriate.

Otter voice notes will transcribe the recorded data and does this by utilizes artificial intelligence (AI) to transcribe audio in real time; however, the software can also transcribe past recorded audios. With the participant’s answers recorded, the researcher will then upload the recorded audio to otter voice notes and the software will begin to transcribe the information immediately giving out a generated transcript of what the participants said. The software can assign speaker names in the transcripts to enable the researcher attach specific answers to specific participants. That will allow the researcher to keep up with the respondents. Additionally, the software will enable the researcher to edit the transcripts at its interface. Through this, it will be possible to search ad highlight the keywords in the transcript, which can be shared with other researcher in future studies.

The semi-structured interview audio recordings are transcribed via Otter voice, and the data is processed via pre-determined coding schemes. Such an approach is called deductive coding and is frequently utilized in qualitative studies to restrict the scope of research and ensure the in-depth analysis of the examined phenomenon (Linneberg & Korsgaard, 2019). Ultimately, the data is further investigated via the content analysis method, and the primary meaning units are determined, including themes, categories, codes, and condensed meaning units (Erlingsson & Brysiewicz, 2017). As a result, the study utilizes a qualitative case study research design, and information from the data collections is processed via deductive coding and interpreted via content analysis.

Significance of the Study

The current study is significant to the individual, organizational, and societal levels and addresses the relevant mindset competencies concerning differences in the pre and post-9/11 military generational eras. Compared to the previous generation, a larger percentage of post-9/11 veterans participated in a combat deployment at least once. Post-9/11 veterans are almost twice as likely as their pre-9/11 counterparts to have served in a combat zone (Parker et al., 2020). Furthermore, despite the growing number of post-9/11 veterans, the topic is under-researched in the academic community; thus, few organizations are aware of the potential benefits (competencies) of the military mindset in the business setting (Davis & Minnis, 2017). From these considerations, it is essential to conduct additional studies to understand the phenomenon further and increase the organizational awareness of these competencies regarding the military mindset of post-9/11 veterans.

The current research examines the potential advantages associated with acquired qualities of a post-9/11 veteran and identifies the overall value amongst the business communities of interest. The study provides data to develop business strategies to comprehensively overview the post-9/11 veteran’s acquired experiences and associated business competencies. The study results also promote positive societal change for post-9/11 veterans and contribute to the academic community by advancing scientific progress in the field. Ultimately, the current study positively impacts the individual, organizational, and societal levels regarding the topic.

The contributions from the research will help YSG to incorporate post 9/11 veteran’s competencies towards taking advantage of the skills to encourage other employees to improve organization performance. Further, the competencies acquired in post 9/11 military years serves to align other employees towards pursuing common organization goals through streamlined decision-making and problem solving. YSG’s business problem will be solved through incorporating military oriented leadership practices, talent management, and as a consequence, the organizational culture. The unique skills for the civilian workforce include leadership, discipline, resiliency, and teamwork. Further, YSG will benefit from the remarked peripheral skill set of the military veterans, including maturity, adaptability, courage, organizational commitment, and trustworthiness. The mission-focused mindset of veterans distinguishes the skills of this group from the civilians it will be essential to thoroughly analyze each of the core competencies shared by generational military veterans.

Definition of Key Terms

The key terms used in the study are:

- Artifacts: According to the Schein Model of Organizational Culture, artifacts are visible organizational structures and processes occurring in the workspace. (Schein, 2016).

- Asymmetric Threat: Threats in which state and non-state adversaries avoid direct engagement but devise strategies, tactics, and weapons to minimize U.S. strengths and exploit its weaknesses (Kolet, 2001).

- Asymmetric Warfare: A type of warfare involves attacking an adversary’s weaknesses with unexpected or innovative means while avoiding his strengths (Hughes, 1998).

- Basic Assumptions: Unconscious, taken-for-granted beliefs, perceptions, thoughts, and feelings. (Schein, 2016).

- Constructivism: A conceptual framework implies the learning-based acquisition of skills and competencies via culture, training, and social context (Johnson, 2019).

- Counterinsurgency (COIN):Counterinsurgency is the use of all elements of a nation’s power—including combined-arms operations and psychological, political, economic, intelligence, and diplomatic operations—to defeat an insurgency. (Maneuver self-study program, Counterinsurgency. n.d.).

- Espoused Values:Strategies, goals, and philosophies (Schein, 2016).

- Military mindset: A state of mind characterized by such qualities as teamwork, leadership, resilience, and discipline, acquired by intensive training, combat exposure, and military experience (Kirchner & Akdere, 2019).

- Organizational culture: A set of beliefs, values, behaviors, interrelationships, and structures unique to one particular organizational entity (Schein, 2016).

- Pre 9/11 and Post 9/11 Eras: Signifies a divide that refers to a time before the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001 (pre 9/11) and the period after the 9/11 attack (post 9/11). (York University, n.d).

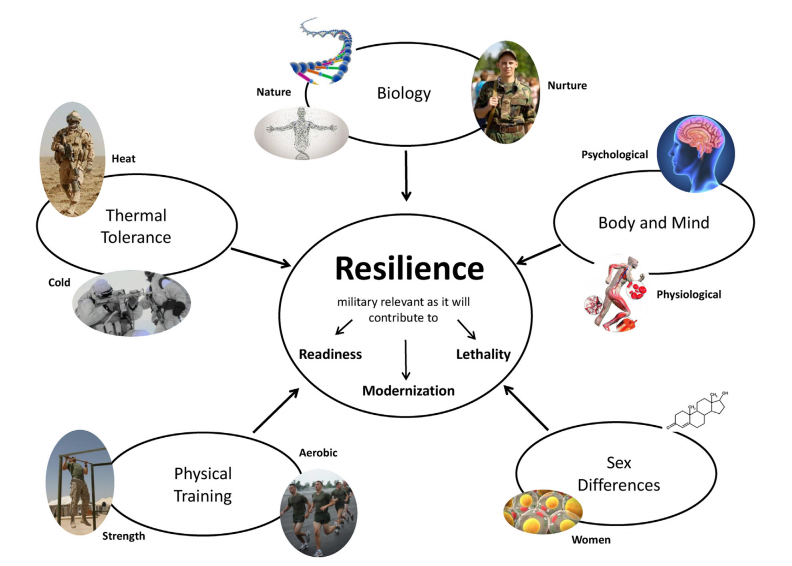

- Resilience: The capacity to overcome the adverse effects of setback and the associated stress on military performance and combat effectiveness. (Nindl et al., 2018).

- Schein Model of Organizational Culture: A conceptual framework of organizational culture emphasizes the impact of beliefs, values, attitudes, and relationships among the workers on the overall productivity and atmosphere of the organization (Schein, 2016).

- Veteran: A person who served in the active United States (U.S.) military, naval, or air service, and who was discharged or released under conditions other than dishonorable.(Staskiel, 2020)

Summary

The U.S. military transitioned to a new paradigm of warfare after the tragedy of the 9/11 attack that combatted international terrorism to defend the nation contributing to the unique perspective of post-9/11 service members. As a result, service members who served after the September 11, 2001 attack have had more intense training regimes, more frequent exposure to combat, and higher deployment rates than previous military generations (Parker et al., 2019). A difference between pre-9/11 and post-9/11veterans is acknowledged in the U.S. military’s transition in warfare and the innate skill sets acquired. However, at present, there is a noticeable lack of research on the mindset competencies of post-9/11 veterans specifically and the potential competitive advantages of the targeted group in a business sphere. Therefore, the purpose of the current study is to examine what competitive organizational advantages exist in the competencies of post-9/11 veterans and what are the corporate benefits of that mindset in a business setting.

The proposed research plan for the current study is to investigate the perspectives and attitudes of the YSG’s employees, exclusive to post-9/11 veterans, HR managers/specialists, and executives. The project utilizes a qualitative case study to ensure in-depth research of the phenomenon and answer the proposed research questions. The sampling size for the project is seventeen participants, and the data collection methods include archival records, questionnaires, and semi-structured interviews. Consequently, the data is processed via deductive coding and analyzed via content analysis according to the two selected conceptual frameworks – Constructivism and the Schein Model of Organizational Culture. The most significant meaning units, such as themes, categories, and concepts, are identified to understand further the perspectives of post-9/11 veterans, HR managers/specialists, and senior executives regarding the topic. The study’s findings may demonstrate the unique nature of the competencies of the military mindset of post-9/11 veterans and if competitive advantage of the target group exists in the business setting, which in theory can have a positive impact on the individual, organizational, and societal levels. Chapter 2 provides a detailed review of relevant literature corresponding to the research topics and themes of the study.

Literature review

Previous research and literature acknowledged that military veterans possess several skills and abilities that are effective in business culture. As a result, it is beneficial to analyze the competencies that post-9/11 veterans and their intrinsic military skills acquired through encounters during the U.S. military transition to counterinsurgency operations against asymmetric threats offered in a contemporary business environment. The nature of the civil-military environment directly emulates the transformational dynamics in today’s business environment. Many organizations operate in a turbulent environment and incorporate constant changes to maintain their competitiveness in today’s business domain. Military veterans have highly developed command skills that are advantageous in business (Benmelech & Frydman, 2015). This study proposes utilizing five themes (organizational culture, leadership, discipline, resilience, and teamwork) to study the context of the post-9/11 military mindset within non-military organizations to enhance various elements of performance or organizational structure.

A literature review reflects that adopting the competencies of the military mindset could be highly beneficial in contemporary business due to the developed and multifaceted skill set of veterans (Nazri & Rudi, 2019). The most significant business advantages include critical thinking, decisiveness, leadership, teamwork, and project planning (Hardison et al., 2017). The linkage of the military mindset and its application in a business setting support the research and analysis of the selected research topic. According to Darwin’s Origin of Species, it is not the most intellectual of the species that survives; it is not the strongest that survives; but the species that survives is the one that is able best to adapt and adjust to the changing environment in which it finds itself (Megginson, 1963). Darwin’s evolutionary theory is an example of an inner logic that has vast cultural influence (Birkin et al., 1997), but the behavior of the most successful is viewed as being opportunistically adaptive during environmental change (Baskerville, 2006). Therefore, the same principle applies in a corporate setting since economics, business organizations, and capital markets are considered to operate like machines: inputs and outputs, controls and regulators (Bakerville, 2006).

Documentation

The literature search strategy sought to use a deductive approach of taking a broad theme and research topic of “leveraging the competencies of the military mindset in business” and narrowing it down to specific applications. For example, reflected in table 1 are the practical applications of the military mindset explored in the context of organizational culture, business leadership, business discipline, resilience in crises, or substantial elements of teamwork.

The use of databases such as Trident Online Library, Google Scholar, JSTOR, Scopus, Science Direct, ProQuest, and Emerald, key terms were searched for military mindset, veterans’ competencies, organizational culture, corporate leadership, post-9/11 veterans, and based on material relevance from a preliminary reading of abstracts. The literature was reviewed for relevancy and fundamental elements of efficacy and reliability: approximately 156 reports, journals, and books were examined for the literature review. Conducted a thematic analysis to categorize the articles based on subject themes about the organization of the thesis and the organization of the literature review (King et al., 2017), which developed a logical and cohesive flow of information from currently available sources based on the analysis. The deductive method of information retrieval will be applied, in which the process of cognition proceeds from broad generalizations presenting a general pattern to single judgments and facts (Charniak, 2014). Initially, the available literature was reviewed to establish a base of the current research in business leadership and management, then transitioned to finding literary sources of a scientific or methodological nature regarding military mindset. The most suitable study design is a case study because of the selected topic and the peculiarities of data needed for its analysis.

An article titled “Action Research vs. Case Study” stated that acase study explores a contemporary prodigy within its real-life context and provides an organized way of observing the events, collecting data, analyzing information, and reporting the results (2019). In the originality/value statement, Kirchner and Akdere (2017) noted, a review of existing literature revealed little evidence of examining the military’s approach to developing leaders, even though employers claim to hire veterans because of their leadership abilities. A dearth of papers exists that considers military strategies for non-military organizations – such investigations strengthen the project and provide some data for comparison and further study.

While a notable lack of literature focused on the post-9/11 era, some insights are provided on the military mindset. For example, Kirchner and Akdere (2017) identify four development strategies applicable in commercial training. Roberts (2018) highlights various principles of military traits that can be compared and contrasted with traditional business management styles. Deshwal and Ashraf Ali (2020) examine theoretical backgrounds that are also relevant. Nevertheless, there are significant elements of information not found in these sources, particularly in the sense of more practical applications to identify the competencies of post-9/11 veterans that are transferable in business. Earlier research is beneficial since the military mindsets tend to change very slowly due to the conservative nature of the organization. As mentioned earlier, many companies hire veterans for their military mindset, but how they are applied in the workplace and for an extensive project is relatively unknown in the current scholarly literature. Therefore, it is advantageous to study the current state of the competencies of the post-9/11 military mindset in a civilian business organization.

Nevertheless, it is essential to narrow down the scope of the work to provide a more in-depth research of the analyzed phenomenon. Therefore, the primary part of the research concerns the identification of certain competitive advantages in business due to the commonly acknowledged qualities of a military mindset. The interviews with post-9/11 military veterans, HR managers/specialists, and senior executives can provide insights into the organizational culture and the contribution of veterans to the company. As mentioned prior, post-9/11 veterans acquire transferable cultural and nation-building skills than their previous military generations. This distinction is heavily under-researched in the academic community (Aronson et al., 2019). Therefore, the primary objective of the current study is to reduce the gap in qualitative research of post-9/11 military mindset competencies and create an awareness of the competitive and cultural advantages of post-9/11 veterans’ acuity.

Organizational Analysis and Benchmarking

The following data reflects a brief overview of the study’s selected organization, YSG, from an analysis of secondary data sources. It is essential to thoroughly examine the organizational structure, hierarchy, human resources strategies, prospect for development, and company competitors. A comprehensive organizational analysis is necessary in many qualitative research methods, including ethnography, phenomenology, and case studies (Lehn, 2019). Ultimately, practice-based qualitative research relies on the deep connection between the researcher and the study participants, and organizational analysis is the initial step that promotes collaboration (Lehn, 2019). Furthermore, the organizational analysis provides a thorough understanding of the work culture within the company and the relationships among the employees. The YSG organization is the sole collective entity for the analysis in the current study; therefore, it is necessary to thoroughly examine the company before conducting the empirical part of the research. Appendix A provides the company’s letter of intent (LOI) to support the study’s research efforts.

Organizational Composition

YSG is a service–disabled veteran–owned small business established in 2008, with its headquarters in Huntsville, Alabama. The company is a professional services company providing customized solutions and management capabilities to federal and civil organizations. The company specializes in training and education, language and cultural learning, operational and intelligence mission support, modeling and simulation, program management and administrative support, integrated logistics, systems engineering, management analysis, human capital, and information technology (IT) services. Its estimated annual revenue is currently $135.2M per year (Growjo, n.d.).

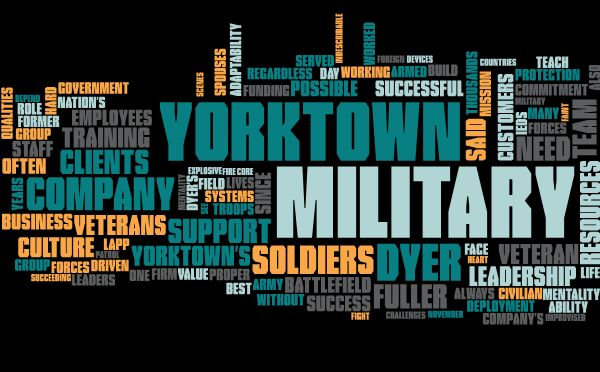

The company traces its heritage to the last major battle of the Revolutionary War, the Battle of Yorktown – from which the name and its inspiration is rooted (Growjo, n.d.). Figure 4 illustrates a word cloud-generated content analysis of YSG’s commitment to doing what is right instead of what is profitable, as exemplified in YSG’s organizational article titled “Succeeding with Military Mentality at its Core”.

The company structure is hierarchical but with adjustments that align to commerce flexibility and responsiveness to international marketplace alterations. Due to such corporate organization, the firm can continuously develop solutions to help the public and governmental enterprises solve their complex and challenging issues. Consequently, the company structure permits the milestone of YSG’s corporate business mission and vision statements that affirm the administration’s strategy. The enterprise’s organization is the concrete manifestation of company policy fundamentals that impact how numerous elements of the business complement and function as a unit.

Structure and Hierarchy

The company has a well-designed organizational structure that aligns with military doctrine. The organization has a functional hierarchy that resembles the type suggested by scholars (Roulston & Choi, 2018). The corporate arrangement is usually flat, equated to several firms that inhibit the functional hierarchical organizational framework. For instance, all primary managers directly report to the senior managers (Davis et al., 2018). Such a business framework maintains a strict order design, which minimizes the administration level to influence concerns on the belief of centralization. The organization’s corporate structure aims to deliver set objectives and drive the organization towards realizing its operational functions. The company’s business approach could also indicate its success in retaining prime employees and maintaining a high-performance culture. The technique addresses all the difficulties its clients experience during their operations in the turbulent global marketplace.

Company Growth

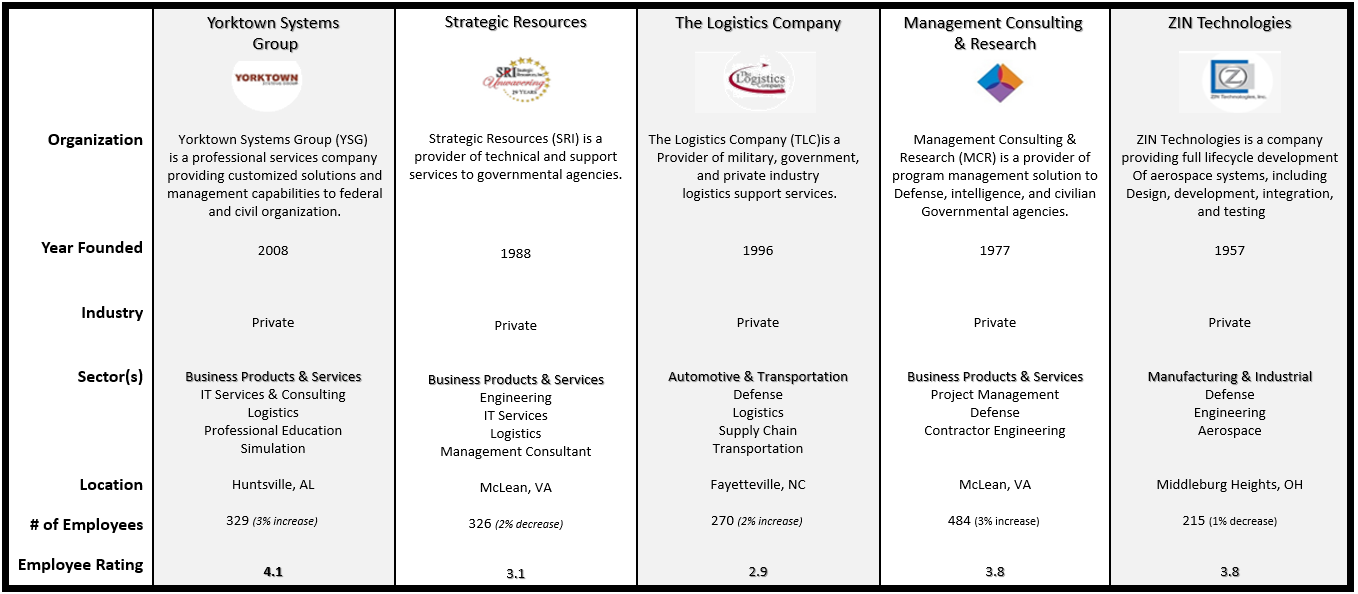

The primary competitors of the YSG organization are Strategic Resources, the Logistics Company, Management Consulting & Research, and ZIN Technologies. From June 2019 through June 2021, YSG hired over 127 employees (LinkedIn, 2021), of which 73% were veterans. The overall number of veteran employees within the company is significantly higher compared to non-veteran employees. These tendencies transparently could demonstrate the positive development of the organization and indicate the contributions of the post-9/11 veterans in the company.

A comparison of YSG and its competitors mentioned above, shown in figure 5, reflected that the company has a similar number of employees, revenues, and provided similar services despite its establishment after its competitors.

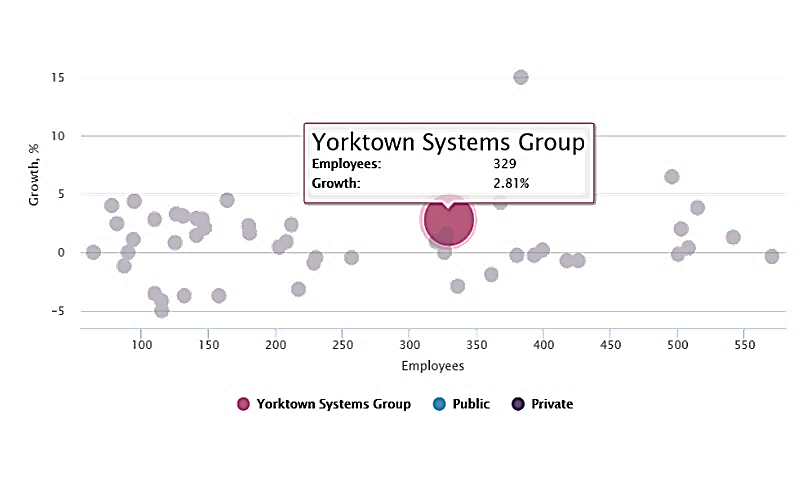

YSG has been operating for the past 13 years and employs 329 employees (CraftCo. n.d.). The relevant aspect of YSG’s establishment after its competitors and its continuing growth in the number of employees is relevant in understanding its sustainable evolution. The company’s high employees rating of 4.1 out of 5 (CraftCo, n.d.) could also imply that employees are satisfied with the organizational culture. As shown in figure 6, a growth rate in the market position of almost three percent is a relatively high rate compared to public and private companies with a similar number of employees (CraftCo. n.d.).

YSG’s workforce, the majority of military veterans, is viewed as the contributing factor to the company’s growth and expanding business categories. The organization’s culture of employing veterans could also indicate that the company is benefiting from the hiring of post-9/11veterans, thus a competitive advantage in its business.

Theoretical Background

The theoretical background commonly utilized theories to analyze the qualities of the military mindset and organizational culture. Schein (2004) stated that culture is socially constructed as founders surround themselves with people who share their values. The two presented theoretical frameworks, Constructivism and the Schein Model of Organizational Culture, provide a comprehensive summary of the potential advantages of a military mindset in the civilian workforce. The former analyzes the origin of such qualities as discipline, resilience, adaptability, and leadership in the military setting with the consequent application of these characteristics in business. The Schein Model is a theoretical framework, which thoroughly analyzes the organizational culture and demonstrates how the qualities of individuals affect the company as a whole. Ultimately, Constructivism and the Schein Model of Organizational Culture constitute the theoretical background of the empirical part of the research and are highly significant for the current study. A thorough description of these theories is discussed in detail in the following sub-chapters.

Constructivism

One concept that consistently appears throughout the literature examined for this research is that the military mindset and leadership qualities are learned (Adler& Sowden, 2018; Kirchner & Akdere, 2017). As discussed below, all military members are expected to command the mindset skills learned through culture, training, resilience, and teamwork. A relevant theoretical framework is a constructivist approach to learned leadership training when applying this standard approach to commercial organizations. In an era of leadership, learning and personal development are critical contributors. The constructivist approach seeks to identify constituent characteristics in developing competency, including psychological, social-cognitive, behavioral, and message productional factors (Johnston, 2018).

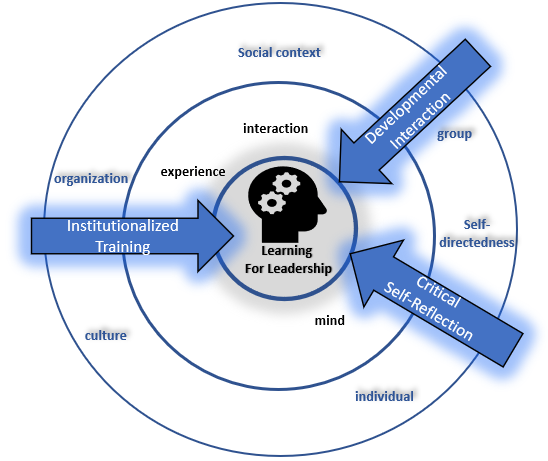

The constructivist approach emphasizes leadership development, effectiveness and evaluates how they perceive and perform their roles and engagement in reciprocal processes such as learning, shared values, responsibilities, and facilitation (Yildirim & Kaya, 2019). Participating in the construction of knowledge allows leaders to make necessary cognitive, behavioral, and practical changes regarding their role in an organization (Johnston, 2018). The critical constructivist approach suggests that the developmental synthesis of all these approaches is required to achieve expected results (Nissinen, 2001). There are mind-centered concepts such as self-reflection and self-directedness at the individual level, while the organizational level encompasses institutionalized training and cultural frameworks (Nissinen, 2001). As shown in Figure 7 below, there are several approaches to acquiring knowledge and applying it to learned leadership.

The importance of the constructivist approach lies in its explanation of how learning takes place. Per Johnson (2019), an active process requires the learner’s involvement at all times. Knowledge is not effectively conveyed when one side imparts it, and the other passively receives the information. The role of the teacher is to inspire curiosity in their student so that they start asking questions and trying to understand the topic in earnest. The learner, in turn, needs to understand the importance of what they are learning and be committed to obtaining the skill set discussed. For that reason, it is essential to gather evidence of the effects of a military mindset on business performance and link the two together in a compelling narrative. This study is a step toward that goal that aims to compile and process the relevant information.

The constructivist theoretical framework supports the idea that a company’s performance is affected by the personal, team, and organizational inputs as well as the processes (Dulebohn &Hoch, 2017), thus, an assumption that personal effectiveness has a considerable impact on a company’s performance. It is also vital to differentiate between the two approaches to constructivism that have been formulated over a period of time. Johnson (2019) claims that these are cognitive constructivism, the theory described above, and social constructivism, which posits that their social context influences one’s learning. The trainer’s role would be to encourage social interaction and provide a cultural context to the subject. However, social constructivism is less appropriate for the topic than its counterpart, which led to its rejection. The military is not necessarily easy to accurately explain in a cultural context, in large part due to its frequent misrepresentation in popular media. Creating a social environment that reflects the military is challenging; therefore, cognitive constructivism fits this study. Nonetheless, it is possible to borrow some elements from the theory, such as organizational culture adjustment requirements.

Applying the constructivist approach to the research question presents an opportunity to explore post-9/11 learned competencies and their application in business settings. Similar to the military organization, said mindset elements can be learned if appropriate resources and culture are in place, and the influences promote critical self-reflection (Hilden and Tikkamäki, 2013). In that environment, it is possible to apply cognitive and social constructivism. The learner experiences the military culture and interacts with more advanced leaders while also interested in learning the method. The military mindset is achieved through a multifaceted constructivist approach, where a combination of culture, experience, interaction, and individual growth contributes to developing valuable characteristics. The key question becomes how to transition that learning model to a commercial environment to achieve a similar mindset in managers and employees.

Schein Model of Organizational Culture

Organizational culture is a common term that typically encompasses an organization’s values and beliefs, ultimately impacting its principles, ideologies, and policies. Schein (2016) proposes that organizational culture takes significant time to form and develop as employees and leadership change, adapt to external environments, and solve problems. As illustrated in figure 8, the Schein framework proposes that there are three levels of organizational culture: 1) Behavior and Artifacts, 2) Espoused Values, and 3) Basic Assumptions or assumed values (Schein, 2016).

Artifacts are characteristics of an organization that are evident and easily perceived, everything from dress code to facilities to public vision. The values are the beliefs of the individuals working in the organization, as thought processes and attitudes profoundly impact the culture and workplace environment over time. The mindset of individuals associated with an organization influences the culture of that workplace. Finally, assumed values that cannot be measured remain hidden but continue impacting the culture – inner aspects of human nature. It can include attitudes such as subconscious racism, sexism, or even practices never discussed but remain an open understanding within an organization (Schein, 2016).

The application of the military mindset in business has to consider these numerous levels of organizational culture. As later discussed, some elements in the military culture are similarly publicly seen and discussed. In contrast, others are implicit and develop with years of focused teamwork, a culture of respect, and the discipline and resilience which define the mindset. Transitioning a military mindset into commercial settings takes time to develop the culture from initial workplace rules and shared vision to the underlying understanding that the organization is a team that strives towards a common objective. Some of it may be counterintuitive to the standard business practices of competition and self-centered individuality, but in time, with layers within this framework, the military mindset is adaptable.

The drawbacks of Schein’s Model are taken into consideration throughout the discussion of organizational culture. Overall, the concept is nebulous and challenging to describe because corporate culture develops spontaneously and is challenging to observe or manipulate. As Gilbert et al. (2018) noted, the model provides an outsider’s overview of an organization’s internal culture, focusing on the outward expressions and artifacts that may not necessarily be accurate. The example they use is that, while an overwhelming majority of all businesses claim they value safety, this commitment does not necessarily manifest in practice since the underlying organizational culture does not promote this value. This model considers the potential discrepancy and factors it into their observations when attempting to judge an organization’s culture, gathering as much information as possible, and obtaining a multifaceted perspective.

It is also necessary to consider that organizational culture is flexible and mutable, changing over time as it adapts to new needs. Campbell (2019) discusses a recent post-Cold War evolution in the American military mindset, which traditionally focused on conventional warfare and direct force on the battlefield. However, this strategy proved fruitless in environments such as that of Vietnam, and senior leaders went against the established culture by considering non-conventional approaches and applying them in practice. As a result, counterinsurgency operations became part of the standard American military protocol despite going directly against the culture (Campbell, 2019). This warfare doctrine also required a shift in the military leadership approaches to make this smaller-scale, more precise operations possible. As such, the military’s culture and its leadership approach have changed over time and are likely to do so again in the future, which means it is essential to rely on current information for accuracy.

The Military Mindset

The military mindset (initiative, adaptability, flexibility, innovation, and creativity) is necessary for the survival of service members in wars/conflicts and the development of organizational culture and is seen as mental preparation for the unknown. Adapting is just as essential to survival in business as on the battlefield, and many companies do not survive over time because they fail to adapt to changing business conditions (Burns, 2013). Solving problems using an out-of-the-box approach is necessary for the military culture and applies to every business unit. An argument of military service and combat activity of service members require a complex of certain qualities forms the professional structure of one’s personality, and at the same time represents the basis of leadership in a team. The most important of them are high intelligence, purposefulness, the ability for psychoanalysis and reflection, resistance to stress, emotional balance, and the ability to manage oneself, empathy, organizational insight, exactingness, professionalism, and sociability. All veterans are trained to do the impossible by their nature and are willing to make the ultimate sacrifice. Both pre-9/11 and post-9/11 veterans have acquired specific skill sets during their military service; however, the difference in their cultural training and combat experiences defines characteristics for forming the competencies in developing their military mindset.

Post-9/11 Veterans’ Mindset

The study’s theme comprises specifically of post-9/11 military mindset in a civilian business sphere; therefore, it is necessary to provide a thorough description of post-9/11 veterans and identify key points that differ from the previous military generation. The increased number of deployments to support a change in warfare centered on winning the hearts and minds of the people; a phrase for a British approach to counterinsurgency that emphasized winning the hearts and minds of the population through securing the support of the people (Fishstein & Wilder, 2012). Therefore, a case that the most significant distinction between the pre-9/11 and post-9/11 era veterans is that the latter has considerably more combat experience (Parker et al., 2019) in a civil-military environment that requires continuous interactions and transactions with tribal leaders and local populous.

According to a survey of U.S. veterans (May-June 2019), approximately 58% of post-9/11 veterans had served in the proximity of a combat zone, as opposed to 31% of pre-9/11 veterans (Parker et al., 2019). Furthermore, about 77% of post-9/11 veterans were deployed at least once, while the percentage of pre-9/11 veterans with similar experiences is 58% (Parker et al., 2019). The current statistics transparently demonstrate the prevalence of combat experience among post-9/11 veterans. Most veterans have agreed that combat proximity had made them change their life priorities, emphasizing teamwork and close relationships with people (Parker et al., 2019). Additionally, approximately 70% of post-9/11 veterans realized that they were stronger than they had initially thought before the combat experience, while only 8% of people mentioned that they had been overestimating themselves (Parker et al., 2019). These changes are noticeable by both military veterans and the public. The statistics demonstrate that about 84% of veterans believe that military service has made them more disciplined than people without combat experience (Parker et al., 2019). At the same time, 67% of civilians also believe that discipline is the defining characteristic of military veterans (Parker et al., 2019). Ultimately, military service is a life-changing experience, and most post-9/11 veterans agree that the experiences have significantly affected their personal and professional growth.

The intense training and exposure to combat build up such qualities as discipline and teamwork. The research states, “post-9/11 veterans are about twice as likely to have combat experience as earlier veterans” (Parker et al., 2019, p. 12). Therefore, it is assumed that post-9/11 veterans possess extensive cultural training and combat experiences than the earlier generations, significantly influencing previous learned generational skill sets, competencies, and qualities.

Post-9/11 Generational Competencies

The study’s theory concerning the generational competencies of post-9/11 veterans aligns with constructivism. The constructivism theory implies that the experiences of the post-9/11 soldiers, such as extensive combat exposure, military challenges in various environments, and teamwork during critical situations, significantly improved generational competencies and allowed the forming of new skill sets. Furthermore, constructivism is generally acknowledged as a practical learning framework for military and defense-oriented personnel due to the vast emphasis on critical thinking and self-discovery (Elstad & Davis, 2017). The approach is based on the concept of “Five E’s,” which are generally deciphered as Engage, Explore, Explain, Elaborate, and Evaluate (Elstad & Davis, 2017). Therefore, implying a more practical perspective on learning and acquiring competencies helps explain generational traits of post-9/11 veterans and why they differ from the competencies of pre-9/11 soldiers. First, more extensive combat exposure implies more military practice, teamwork training, emphasis on an objective-oriented mindset, and higher deployment rates (Parker et al., 2019). The practical efforts constitute the core concept of constructivism, and the more extensive amount of preparation and actual combat explains the generational traits acquired by post-9/11 veterans. Furthermore, constructivism suggests that people might build up their competencies based on the example of previous generations via learning perspectives (Sookermany, 2017). In this sense, the experience of pre-9/11 soldiers could enhance the overall skill sets and qualities of post-9/11 veterans through communication and training.

Secondly, the military missions have shifted from general training to counterterrorism objectives, commonly associated with more risks. The specific preparation also includes the overview of advanced technological devices, such as drones and special ammunition, hostage rescue, and emphasis on softer skills, such as decision making and adaptability (Mir, 2018). Many of these qualities are highly useful in the civilian workforce, making post-9/11 veterans’ competencies better suited for today’s business environment.

Lastly, post-9/11 veterans constitute the most diverse group of soldiers in American history. The tragic events of September 11, 2001, left a deep imprint on people of different backgrounds and beliefs (Stone, 2020). As a result, the post-9/11 military enlistment consisted of the most diverse candidates, including people of various cultural backgrounds, races, genders, and ages (Stone, 2020). This variety allowed for a more comprehensive perspective exchange, which also differentiates the overall experience of pre-9/11 and post-9/11 veterans (Stone, 2020). Ultimately, the differences in competencies between the two groups can be explained by various degrees of combat exposure, military preparation, and diversity of the units, which align with the constructivism theory.

Leveraging the Post-9/11 Military Mindset

Despite many shared generational military competencies, post-9/11 veterans demonstrate a more extensive range of skill sets than the previous generations. As mentioned before, this phenomenon primarily occurred due to the change of national military approach after the September 11 attacks, which led to more combat exposure among the soldiers (Parker et al., 2019). The wars and counterterrorism operations in Afghanistan, Iraq and other parts of the Middle East have cost the lives of American soldiers (Crawford, 2018). Furthermore, post-9/11 veterans experienced higher deployment rates, more critical situations, and organized warfare, significantly affecting their worldviews and perspectives on teamwork and military combat (Parker et al., 2019). Therefore, the study suggests that the intense post-9/11 military actions and preliminary training have formed new generational traits of post-9/11 veterans that can be effectively used in the civilian workforce.

Private businesses serve various forms of customers, while the military answers to elected officials. As a result, the military has adopted a conservative attitude that emphasizes the unpredictability of the future and the need for the organization to rapidly and effectively respond to changing circumstances (Maurer, 2017). Conversely, while the future is unpredictable in the private sector, forecasting product demand is still possible. However, the military ability to create robust organizations and handle crises can be invaluable for businesses since, despite their rarity, such events can have catastrophic effects on the organization. The possibilities and potential benefits of employing or retaining post-9/11 military veterans in business organizations could improve leadership practices, talent management, and as a consequence, the organizational culture.

The last significant determinant of the military mindset is the exact relationship between the military and civilians. As Corbe (2017) noted, while the military is subordinated to the civilian sector at the top level, the relationship is not as hierarchical and poorly understood at the operational level. The military is a tangible entity that exists abroad and often becomes involved in local initiatives, where sectors rely upon the other to solve issues and improve the quality of life. The families of military members also have to be considered, as they can often form substantial communities in and of themselves. As a result, while military members are used to their local culture, they are not ignorant of the civilian locations’ broader culture. Barring complicating factors such as an extended foreign tour, adaptation to new conditions nor environments may not be excessively challenging.

Differences in Military and Business Settings

Work organization and labor division have changed significantly, leading to more people focusing on outcomes based on adequate knowledge and research (Lyskova, 2019). Under the knowledge economy, the focus is to understand how experience and education (human capital) act as a business product or productive asset to be exported and sold to create profits for the economy, businesses, and individuals (Gregg, 2018). This aspect of the company depends on people’s intellectual capabilities and not physical contributions or natural resources. It is unknown whether business success requires the same core skills, values, and leadership qualities formed in the military; therefore, it is necessary to understand the specific differences between the two environments and the challenges businesses face.

Military Veterans Generational Shared Business Competencies

As mentioned before, all veterans share some business competencies regardless of their military generation. The unique skills for the civilian workforce include leadership, discipline, resiliency, and teamwork (Pollak et al., 2019). Nevertheless, employers also remark the peripheral skill set of the military veterans, including maturity, adaptability, courage, organizational commitment, and trustworthiness (Pollak et al., 2019). The mission-focused mindset of veterans distinguishes the skills of this group from the civilians (Dillon & Advocate, 2017). One of the study’s conceptual framework models is constructivism. Its central idea is that human learning is constructed, and learners build new knowledge upon the foundation of previous learning. Therefore, it is necessary to examine prior generational competencies that post-9/11 veterans used as a foundation to further new learning before the post-9/11 warfare transition. Consequently, it is essential to thoroughly analyze each of the core competencies shared by generational military veterans.

Military Culture

The U.S. military is considered a unique organization with the inherited responsibility of protecting and defending the nation and its interests. During the Revolutionary War, the military has acted, fought, and thought differently from the military inception. It takes a particular type of individual to place the needs of the country over self. Since the beginning of military service, these differences, which focus on achieving the mission in unorthodox and unique ways, have become the basis of the military culture. It is a crucial aspect that makes the military successful in accomplishing challenging tasks in extreme situations.

These mindset changes are not easily undertaken in a business, but the successful leverage of a similar culture may create a competitive advantage. A strong organizational culture is a common aspect of successful organizations. Some agree that the highest company’s goals are to have the proper cultural priority. A company desires leaders who understand and appreciate the organizational cultures and will ensure employees understand its cultural identities.

The success of changes in today’s military rests with the distinct culture and the transformation to asymmetric warfare. Post-9/11 soldiers possess a unique mindset acquired through the transition in warfare, where the social, cultural, and political dimensions’ parallel today’s business environment (Pollak, et al., 2019). As mentioned prior, some of the notable qualities include leadership, teamwork, work ethic, adaptability, organizational commitment, initiative, and other characteristics highly relevant for business settings (Pollak et al., 2019). The unique culture is the dedication to achieving the mission and the unconventional approaches used to solve problems. Although some may argue that values do not focus on the people but the company and its objectives (Felipe et al., 2017). These key cultural traits are shared across the military enterprise, regardless of the mission, rank, unit, or related factors. Culture is organic and intangible and has given various military leaders the management tools to influence culture, including rigorous assessment and selection, complex missions, strong leadership, and training processes. Like every successful organization, culture is integral to the military unit and how it achieves its mission.

The military organizational culture is not necessarily the only example to follow for civilian organizations in some regards. As mentioned above, military culture often tends to be static, waiting for internal actors to reform it also passively rejecting any such attempts. Breede (2019) highlights this issue and recommends that the military regularly revisit its organizational culture to ensure that it matches the evolution of social discourse, with the assessment preferably done by non-military personnel. The overextensions in which the military engaged after 9/11 serve as an example of the issues that can manifest should the military act without constraint or self-reflection. Actions ensure that it can constrain itself. This mechanism improves the military’s current organizational culture and reduces the chances of it deteriorating over time.

The military mindset begins with the organizational culture, which business leaders can learn and embrace to ensure optimal performances. In the military, the accomplishment of the mission and training shape the culture; thus, the same applies to business organizations. Their mission and training can shape culture and influence organizational performances. Selecting is about finding the right individuals and molding them to the common culture. Across the military, no matter the specific service or component, the culture is one where one does not quit until the goals or missions are achieved. It is not about finding the best people but more about finding the right individuals. It is finding the right individuals who have the right key competencies and are trainable. A case of consideration is the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks. Before September 11, 2001, the training and assessment plans still had the same individuals, but post-9/11 veterans’ immediately adapted to the new phase of warfare. The persistent ability of an individual or unit to constantly sense its environment for change and to agilely respond to actual or anticipated changes in the environment in a way that improves its operating effectiveness or survival in that environment (Burns, 2013).

The military looks for intense dedication from teammates with a strong desire to succeed in an ambiguous environment and individual fortitude. The military has high-quality individuals and strives to train, motivate, and mentor them effectively. These individuals are what the military seeks and are also highly desirable in business (Pollak et al., 2019). In the recent national survey, approximately 87% of employers have transparently asserted that the military skill set is relevant in the civilian workforce (Pollak et al., 2019). Thus, the increasing interest in hiring post-9/11 veterans has become one of the most discussed topics in business.

Leadership

The military is known for stimulating and developing leadership qualities in service members. As a result, many military veterans pursue management roles in organizations or begin as entrepreneurs. Several studies introduce the idea of using military leadership practices in non-military organizations to improve their performance. The main argument put forward by Bungay (2012) is that there is the task to analyze the possibility of building synergy between management, leadership, and command, in which the experience of military veterans who took part in hybrid wars. This synergy is valuable to introduce the best practices of military leadership. One of the more recent investigations written by Kirchner and Akdere (2017) explores the possibility of using military leadership development tactics in commercial training. The authors suggest that some traits of military leadership development can contribute to human resource training. In particular, Kirchner and Akdere (2017) highlight the establishment of core values for all employees and a dynamic supervisor-employee relationship. Roberts (2018) presents the twelve principles that should guide modern military leadership, describing such concepts as leading from the front, having self-confidence, fostering teamwork, being decisive, and others. This recollection of the necessary traits from a person with actual command experience can be used in the study as a foundation for integrating military theories into the corporate setting.

Military leaders do not rely solely on their authority and right to give orders in their work. Stebnicki (2020) states that reliance on an authoritarian or transactional leadership style in the military does not produce benefits beyond the short term. Those who succeed in their positions will typically listen to their subordinates and accommodate differences of opinion among their subordinates. Regardless, they will also be ready to act quickly and decisively when the situation calls for it, expecting orders to obey immediately. This duality of approaches is vital to the success of the military force preparation to act and an organization that needs to sustain itself in peacetime.

The military provides individuals with critical skills needed in leadership, some of which are discussed in other themes, such as the ability to overcome obstacles, teamwork, weighted risk-taking, and discipline. The military mindset is replicated in team spirit and solidarity in the business environments where the individual can take the leadership role (McDermott et al., 2015). The military uses a continuous and consistent approach to leadership development, expecting competencies from all its members regardless of actual position or authority. However, those in positions of power in the military have much more consequential roles, where mistakes can cost soldiers’ lives and present national security risks. Therefore, the development of leadership competency through the synthesis of knowledge, skills, and abilities is a holistic model of development that can be applicable in non-military organizations (Kirchner and Akdere, 2017).

Nazri and Rudi (2019) argue that leader paradigms emphasize attributes and traits crucial in key settings. Furthermore, military leadership commonly follows the guidance, doctrines, standards, and regularly updated principles, allowing development and innovation. The authors proposed the military leadership framework as reflected below in figure 9.

These changes often come from within the organization, as demonstrated by the example above. While innovation is sometimes stifled in the military, it is also adopted once it shows its effectiveness. Many of these traits are effective in complex, dynamic environments, which can be seen in the business context (Pollak et al., 2019). Qualities such as confidence, adaptability, emotional stability, intelligence, decision-making, and competence are crucial for a leadership organization in virtually any context. They are promoted in the military with substantial effectiveness, especially considering the turnover system that exists in the sector.

A remarkable aspect of military leadership lies in its lack of dependence on individual leaders. According to information gathered by Castro (2018), the average military leader stays in the same position for two years or less before departing. Transitional periods are frequent, and the military has to handle them effectively to remain a competitive force. This tendency is substantially different from that demonstrated in the private sector, where, especially at smaller companies, a leader can stay in the same position for periods that can last for decades. With that said, it also means that military leaders are used to taking stock of a situation quickly and devising an action plan. This quality can be invaluable for situations where a leader needs to be rapidly introduced to an environment to make changes. Therefore, the ability of military leaders to operate in the long term needs additional investigation.

The military necessarily promotes long-term planning beyond its highest leadership, which maintains parity or superiority with current and emerging threats to prepare for several theoretical scenarios. However, these leaders are long-term military individuals who are unlikely to leave their positions to take a job at a private company. For the lower-level personnel consideration in this study, the primary focus is to accomplish the mission at hand in the most effective manner possible. However, the military is aware of the issues related to short-term orientation. This tendency can create stringent policies to relieve leaders who manifest misconduct in their duties (Szypszak, 2016). As such, military leaders expect to operate in the long term, though the competence is not necessarily being actively promoted and reinforced.

Overall, while exclusive training in military-style leadership is likely not sufficient for success in a civilian environment due to the different purposes and divergent evolution of the approach in the two sectors, it can complement more conventional competencies. Currently, there is little overlap between them or understanding of how military styles enhance private-sector leadership (Kirchner & Akdere, 2017). However, it stands to reason that applying the competencies veterans learn can benefit an organization, especially in requiring change. Therefore, it is reasonable to examine the specific application of post-9/11 veterans’ competencies to demonstrate the strengths of the skills they learned in the military without undermining the organization’s performance.

Discipline