Over centuries, the word soldier has been perceived as a masculine figure in an army uniform. It is an inclusive term for both men and women in the military. Storytelling mentality and history have always favored men as the crafters of the art of war. Women’s contribution to the war is more often sidelined, understated, forgotten, and their stories are not told even though many of their lives have always been defined by wars. It is factual that women have always directly or indirectly played crucial roles during wars. For example, when men were fighting overseas in World War I and World War II, women more often than not stepped into their shoes to fill their gaps. Throughout the history of wars, women played integral roles, from knitting for Victory to espionage roles which impacted the place of women in today’s military systems.

At first, women’s role during World War I was highly undervalued. Many people were against the use of women in wars as they were viewed as weak creatures that should not have been exposed to war fronts. As the war progressed, they proved their prowess through their courage, extraordinary effort, and sacrifices that increased morale among their fighting men. It led to their recognition and appreciation as effective elements in wartime. While tens of thousands of women volunteered as field nurses and took up other roles during World War 1, an inevitable urgency arose in 1939, a major turning point in their place in the military and out of the military. They were assigned espionage roles, combat duties, resistance, and, more importantly, nursing roles at the frontlines. During the American Civil War, Clara Barton risked her life to support, supply, and treat wounded field soldiers and founded the American Red Cross.

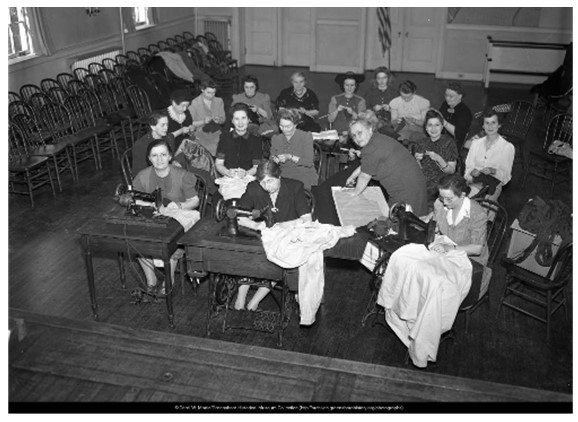

Knitting and Sewing for Victory in World War II

In the American homeland during the Second World War (1941-1945), knitting was a hobby and a preoccupation aimed at helping American soldiers at the frontlines to keep warm. Knitting was preferred to machine-knitting and sewing as it was deemed cheap with quality, lasting products for the soldiers. It was carried out by everyone who was not at the war front, mostly women. A popular magazine on November 24, 1941, carried instructions on how to knit vests to help the Americans at war. Knitting provided a form of help to people at home. Further adoption of knitting by the Americans occurred when America started their entry into World War II. Knitting gave comfort and a warm environment for the soldiers and a calming distraction for those who were knitting. Sewing and complex knitting provided a distraction from the effects of war across Europe. Injured soldiers from the war were also taught how to knit as therapy for post-traumatic stress.

The knitting efforts of the Second World War were exclusively carried out under the guidance of the American Red Cross. The American Red Cross was mandated by the Production Board of War as a sole clearing entity for knitting and was prioritized to receive wool ahead of everyone else (DPLA, n.d). The American Red Cross steered a new occupation of sewing among the women of America. Knitting was one of the core-mandate assigned to the Production Corps, the largest volunteer group. Women also carried out knit for Victory in other auxiliary chapters to the American Red Cross. Seattle city became a hub for garment production across America through sewing and knitting as opposed to machine knitting.

Other than Knitting for Victory, knitting was also used as camouflage and secrecy of espionage. They were spying by planting older women to overlook railway supply yards while knitting. Coded messages were conveyed to the soldiers through knitted knots in patterns that they well understood. British Intelligence Platoons effectively deployed undercover women to identify and report enemy positions. Knitting as an effective weapon rather than a hobby during wars was a patriotic duty by millions of citizens across Europe, America, Australia, the United Kingdom, and the allied nations.

Women Mobilization Propaganda

The Nazi Party legislated male-centered policies that assigned women secondary roles to those of the men in Germany. The German authorities put extensive propaganda across the country to keep women at home away from other duties. Nazi ideologies obliged women to be submissive to their husbands and childbearing tools. Men and women were viewed and depicted differently based on sex superiority and widely communicated in government pronouncements, rallies, and propaganda. The policy portrayed a woman as the Mother of the Country in an attempt that corrupted them into believing they were being favored. On the other hand, men were viewed as shields that defended Germany’s sovereignty and provided labor in German industries.

At the start of World War II in 1939, the Nazi Party needed women to fill the labor shortage since most men took up arms to defend Germany against their enemies. Nazis assigned them new roles as workers away from the previous portrayal of Mothers of the Nation. Their news roles were designed to make up for the reduced labor force based on the changing marriage status and racial categorization. Germany became desperately in need of resources which led to the recruitment of hundreds of thousands of females into the auxiliary units of the military. By 1943, they were authorized to serve in the anti-aircraft platoons. Women were trained on using anti-aircraft guns, but Nazi propaganda barred them from weaponry use. The Nazis late experimented on creating an infantry group for females by 1945 due to the desperate need for soldiers and a war that Adolf Hitler was losing.

Mobilization propaganda was more rigorous in the United States than in the Nazis’ Germany, as figured in America’s mobilization success and failure by the Germans to enlist women into their ranks for World War II participation. Women in United States propaganda were regarded as an ‘arsenal of democracy and were involved in remote support through needing and tending to the duties left behind by men. Thus, American women managed to retain their traditional roles even in a war crisis, which largely determined the superiority of American military attempts over the German ones (Leila, 2015). Even though the United States never involved women in active combat during the Second World War, the success of European female combatants led to the integration of American women into the military. American women were trained in searchlight units, but they were never integrated into combat duties due to fear of backlash from the population. Subsequently, the army created the first unit, the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps (WAAC), which later formed the regular Women Army Corps in 1943. American Women were set to the skies during the Second World War, where they were trained with military aircraft to offer support to the male pilots. In both American and Nazi women’s mobilization propaganda, masculine selective bias dominated where their enlisting in the war was a normal phenomenon compared to females. The dynamics and desperate demands of the Second World War changed the ideology of male chauvinism and military bias. They provided a pathway for the integration of women into the military and assigned those roles that were deemed masculine.

Medical Women during World War I

Medical education among women was always met with cold feet for a long time. Universities and hospitals were reluctant to give them a chance, even by 1914. With time, they were admitted with skepticism into lowly regarded professions such as gynecology and assigned dispensaries. As the world war broke out in 1914, there was an urgent need for female doctors who were needed to do civilian work since most qualified make doctors were assigned duties at the war front lines. The First World War brought triumph to female doctors who were given the chance and vacancy to serve due to the increased demand. The War Office initially barred women from military hospitals as they were thought they would not offer services of the same strength as their male counterparts (NLM, n.d). Due to increasing pressure for medical services, women were admitted though their terms of employment were different from their male counterparts since they were non-commissioned (Leneman). Despite their unofficial status, “[women medics] coped admirably with military surgery, not to mention infectious diseases, imprisonment, guns and bombardment” (Leneman, p.169). Thus, women became full-fledged participants of medical effort in war times, though their role was not initially acknowledged.

In April 1915, an old workhouse was assigned to women doctors who acted as a military hospital. Female doctors’ atmosphere was first described as disapproval, curiosity, humor, and obstinate hostility to others. On the Western Front, the dire need for doctors in April 1916 prompted a desperate request for more doctors in Malta (Leneman). The intervention of the Medical Women’s Federation sent out 85 female doctors to help in the situation. Progressively in April 1917, Britain’s establishment of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps gave a chance to the leadership of a female medical doctor by the name of Dr. Chalmers Watson.

By 1918, the Federation initiated sub-committee recommendations designated to fight injustices in the military. Female doctors in the army yearned for commissioning, official uniforms, and being granted missions overseas as commissioned officers with proper ranks. By November 1918, the quest to grant commissions in the army to female soldiers was denied by the House of the Commons. After that, campaigns for equal rights and pressure on the War Office concerning women medical doctors would see a policy change that guided the commissioning and integration of the female medical corps. Compared to the females, male doctors were highly favored from the start of medicine and given preferential treatment in the army and the air force. The male gender was highly decorated and was given a chance effortlessly, while female doctors had to work their way up to the current state.

Mental Impact of War on Women

Away from their contribution to the peace-making process, women are overwhelmingly affected by the psychological consequence of the war differently than men, regardless of their position in the war. There are multiple roles assigned to women during the war, including motherly and wifely roles coupled with military duties as soldiers on both war fronts and logistics, ammunition makers, and commercialized/forced sex workers. Turnip (p. 10-12) outlines such women’s roles as soldiers, military production workers, and resistance fighters. Although war is regarded as a “men’s affair,” the impact of war creates an enormous psychological effect on women. In her Many Faces article on Women Confronting War, Jennifer Turpin (p.10-16) evaluates three titles: the response of Women to war, Current debates, and the impact created by the war on women.

Women causalities are a common phenomenon in war. These are females who are killed or injured in war. Physical disability is a prerequisite to mental disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorders and post-war depression. Women easily become refugees during wars. The majority of the refugees are women who have through devastating situations. The refugee status exposes most to mental torture resulting from lack of food, safe social amenities, and government harassment (Turpin). Young girls were raped, impregnated, and gave birth to babies whose fathers were a mystery. Such violation of dignity is mentally devastating, leading to suicide, anxieties, and mental depression among women. Institutionalized rape by security forces was used in Sri Lanka as a weapon of ethnic cleansing and a humiliating tool for women.

Frontline female soldiers suffer a great deal of psychological trauma. Female combatants are socially withdrawn from their loved ones, requiring social re-integration after wars. The re-integration incorporates a gender-specific process of re-establishing civilian identities and social relationships. Ex-combatants are faced with emotional and family interrelationship difficulties that cause deep mental struggles, violence against other members of the society, persistently being overlooked, and stigmatization. This, in turn, causes intense psychological trauma, anxiety, self-denial, and dissociative personalities.

Women were highly vulnerable to sex trafficking and sex slavery during wars—the physical repercussions of trauma results in the mental breakdown of an individual. Unrecognized and untreated sexual trauma gives birth to psychological distress. Sex trafficking as a women’s right violation occurs hand in hand with domestic violence, whereby women are used as objects to fulfill sexual desires. Moreover, sex trafficking provides ground for commercialized prostitution where women are owned by specific individual masters and sold to the highest bidder without consideration of the personal needs of women. Apart from economic and social hardships brought by war, extreme traumatic experiences during wars adversely impact the mental struggle that women go through as they cope with the war environment.

Gender and Warfare in the Twentieth Century

Traditionally, the roles of women in the war were as victims. Since the start of the First World War in 1914, the evolution of women in the theatre of war has evolved significantly. From the sidelines working in field nursing, espionage, knitting, and support, women have undertaken active military duties and rose to fight for the cause and against oppressions. Chinese women who lived under an oppressive regime joined the great revolution in china in different roles, which led to their liberation.

While in many roles such as war combatants or medics women’s effort equaled those of men, the harassment and outrage they were often subject to was at the heart of many war crimes. Thus, women were raped at homes and refugee camps; their voices unheard in the cacophony of military effort (Kaufman and Kristen). Kaufman and Kristen provide a sketch of instruments that could be used to reduce those crimes that include military tribunals and court marshalling. Moreover, the acknowledgment of women’s role and their significant contribution to military actions would promote respect and esteem needed to reduce the number of war crimes against women.

During the Second World War, Britain faced a challenge of sexuality within the Women’s Army Corps. Many lesbians saw the military as a haven for them. The problem of screening before enlisting led to an influx of lesbianism. Neither the Army nor the Navy developed policies concerning sexual orientation disorders. Some women were attracted to war units not by the desire to inflict losses on the enemy but by the possibility to feel masculine in a man’s uniform.

The mention of insurgency creates a picture of men resistant to government ideologies. However, women militants were actively involved in wars from Peru to Colombia. Women participated in large numbers during the Maoist movement, a rebellion against the government in 1980. In Colombia, FARC rebels have fought guerilla warfare since 1964, which involved large numbers of women. In the Soviet Union, women were actively involved as tank drivers and fighter pilots and were part of the infantry units of the Soviet states. In Japan during World War II, women were actively involved. Japan’s women were also actively involved as weapons during the Battle of Saipan. In short, the twentieth century saw increased involvement of women in liberation wars, revolution wars, and open insurgency against the government of Colombia and Peru.

Integration of Women into Combat

The Persian Gulf War brought women’s active involvement in military roles into the limelight. Through mass media platforms, women’s performance in the military was evaluated and found to be equal to their male counterparts. The war became an eye-opener for the enlisting and involvement of women in war and combat duties. Having women in combat, which was formerly concealed, has been hailed as an achievement of a century.

From ancient wars in Greece up to the post-Persian Gulf War, women’s combat abilities constantly evolved in physicality and emotional strength during combat. Social cohesion within war units and family relationships. Differentiation of combat, a weaponry battle for Victory, and war, a large-scale armed struggle between warring groups, provided a definition that allowed the placement of women in combat duties in an integrated system (Gale Academic OneFile, 2001).). The impact of women from historical wars to the Gulf War necessitated their enlisting of capable women and their involvement in military duties across the military units.

Initially seen as victims and behind-the-lines workers, gradually women became seen as equals in the military effort. Nicole (p. 5-27) discusses how the perception of woman’s roles changed from the one that necessitated care and attention to battle actors and perpetrators. Women have always been regulated in combat under an unfounded pretext, and American society believes that women should not be involved in combat duties. Equal opportunity in military enlisting has been demonstrated over time, whereby 90% of military roles are open to everyone regardless of gender identity and sexuality.

The transition of Gender Roles in Modern Warfare

Changes in gender roles for women are common in war. Women have struggled with recognition as integral and equal members of the community and gender and sexual identity struggles. Society undervalues the role played by women in the community despite labeling them as mothers of the country. Women are often barred from political and social involvement by the Patriarchal nature of the social systems, thereby depriving them of an opportunity to contribute to change. In peace deal negotiations, women are more often barred from attending despite their peaceful and collaborative attitudes (Kaufman and Kristen, 2010). This has often been associated with the gendering of conflicts through acts of rape and sexual violence and women’s activism during conflicts. In conclusion, the history of warfare depicts a gradual integration of women in a dominantly patriarchal society, from housewife duties to active combat roles in today’s military.

References

Baker, Aryn. “A Climate solution lies deep under the ocean—But accessing it could have huge environmental costs.” Time, 2021. Web.

Digital Public Library of America. (n.d). Women sewing and knitting. Web.

Gale Academic OneFile (2001). Women at war: Gender issues of Americans in combat.

Leila, R. J. (2015). Mobilizing women for war: German and American propaganda 1939-1945. Princeton University Press.

Leneman, L. (1994). Medical women at war, 1914–1918. Medical History, 38(2), 160-177.

Lois, L. A. & and Jennifer E. T. (1998). The women and war reader. Consortium on Gender, Security and Human Rights.

National Library of Medicine. (n.d) Medical women at war, 1914-1918.

Nicole, D. A. (2004). Women and war in the twentieth century. Routledge.

Kaufman, J. P., & Kristen P. W. (2010). Women and war: Gender identity and activism in times of conflict. Lynne Rienner.

Turpin, J. “Many faces: Women confronting war.” The women and war reader (1998): 3-18.